How to relax perception through mushrooms

In a School of Optometry lab at UC Berkeley, Sean Noah muddles pictures of doves. He extracts all their colors, erases every remaining gray, and clouds them with black spots. The distorted images, put together one after the other like frames in an old movie, portray a flying bird.

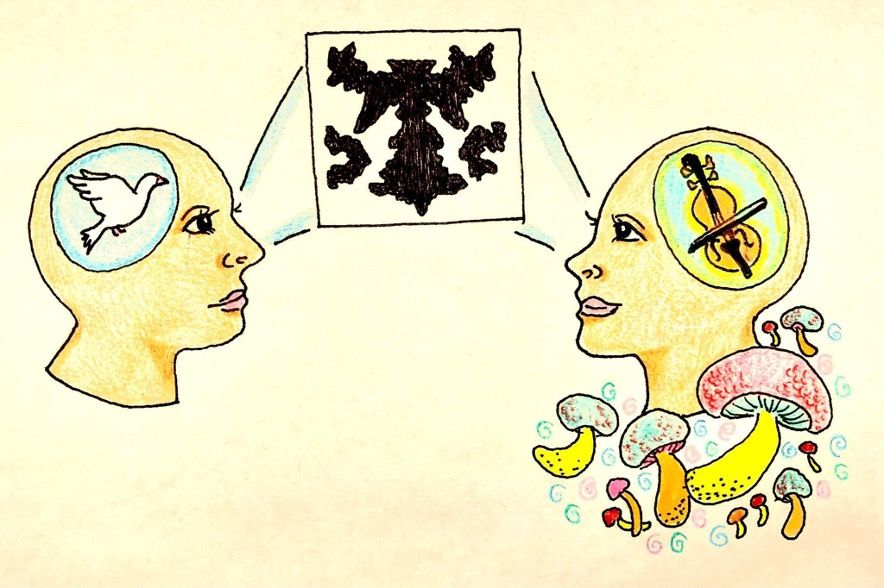

The apparently meaningless blotches covering the stained dove then morph into a cello. What was once a bird is now an instrument.

This change in perception occurs for only some viewers at some times and depends on first impressions. If the brain sees the dove first, it will most likely interpret the image as a flying dove until the end of the sequence by predicting what will happen next.

"If you're not on psychedelics, you are going to be able to predict all the way through that it was a bird," says Noah, a postdoctoral researcher. But if you are on psychedelics, his theory is that the brain will not be able to predict as well as it usually does.

This Rorschach-like sequence of images is one of the hundreds of visual illusions that will be used in an upcoming study at UC Berkeley to understand how psilocybin, the chemical compound in magic mushrooms, affects visual perception. This research project, one of the many in the United States amid the recent boom in psychedelics research, will characterize how psilocybin affects the human brain.

Scientific interest in psilocybin and other psychedelics has spiked in the last few years following the prohibition of these substances in the late 1960s. In 2022, 136 peer-reviewed articles were published in medical journals on psilocybin and its effects on human health; that is 108 more than in 2017 and 126 more than in 2012, according to the National Library of Medicine.

The majority of research aims to test the efficacy of psilocybin in treating patients with mental health disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and alcoholism. For example, just six months ago, researchers at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine found that psilocybin therapy may help treat alcohol addiction. Their study, which involved 93 individuals, concluded that patients who were given psilocybin reduced heavy drinking by 83 percent, unlike those taking placebos who reduced heavy drinking by 51 percent.

There are also a number of studies that want to simply unveil what happens in the brain after taking psychedelic mushrooms. Out of the 51 active studies in the United States doing clinical trials with psilocybin, seven are on healthy adults. Johns Hopkins University, for example, is testing the effects of psilocybin on creativity, memory, and dynamic thought; the Washington University School of Medicine is mapping the whole brain under the effects of psilocybin for future clinical research.

The visual perception study currently being conducted at UC Berkeley is one of these seven studies. Michael Silver, a professor at the Herbert Wertheim School of Optometry & Vision Science and Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, and the director of the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics, is leading this research.

"The goal is not just making discoveries about the brain," says Silver. "But, also, to use that information to design more effective therapies.”

Recent research shows that the visual cortex, where visual processing occurs in the brain, has a dense concentration of one serotonin receptor (the 5-HT2A receptor) that is associated with the psychedelic experience. Classical psychedelics — psilocybin, DMT, LSD, and mescaline — act on this specific receptor in the brain. By analyzing the visual cortex, researchers hope to generalize and predict what happens in the whole brain.

"The fact that there's a lot of 5-HT2A receptors in the visual cortex means that the visual system might be a good place to look for the effects of psychedelics in terms of large-scale neural activity," says Noah, who holds a doctoral degree in psychology and is a postdoctoral researcher in Silver’s lab.

Noah’s role in the project has been to design the pictures that 80 study participants will view when the visual perception experiments start in the next few months. The idea is to show them a sequence of images that can be interpreted in two ways — as a bird or a cello, for example — and measure how psilocybin affects their perception.

The theory guiding this research is that psilocybin does not alter the optics of the eye: it does not affect the retina, the iris, the cornea, or the optic nerve. Rather, psilocybin and other psychedelics, according to Noah, relax the part of our brain that organizes and makes sense of visual stimuli, freeing the brain of the constraints of everyday accustomed interpretation.

According to modern psychology, the human mind is not a blank canvas painting itself with impressions from the world. Instead, we play an active role in what we perceive. Sight is a combination of the stimuli that hit our eyes and how the brain puts them together.

If the theory is right and psilocybin does relax how we interpret and make sense of the world, besides giving us a further understanding of how our brain works, the results could also help explain the promising results this substance has shown in treating patients with depression.

"Depression may be an example of this inescapable negative interpretation of the world that you can't escape from," says Noah. "If psychedelics' mechanism of action is to relax that interpretive part of your brain, allowing new interpretations to form, then they can eventually help you escape these negative loops."

"With therapy, psychedelics can reduce the dependence on these internal narratives of people's self-identity and can help rebuild new ones that are healthier," says Silver, who gave a seminar on the subject in September as part of the Science at Cal lecture series.

After getting their final approval from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in November, the team has all the required permits and is ready to begin enrollment, according to Noah. They are currently deciding how to select the 80 study participants who will receive small doses of psilocybin.

"We're still deciding between a broad recruiting, with flyers on campus and around the city, or a targeted recruiting by reaching out to affinity groups that guarantee a diverse population," says Noah. The idea behind this, Silver says, is to have a universe that is "truly representative of the society that we live in."

Although the trials are expected to begin in the first months of 2023, the team's ambitions go beyond. They are planning a new study to look for the effects of higher doses of psilocybin.

"We are looking ahead," says Noah. "We now have the experience and want to find lasting perceptual changes on visual perception caused by psilocybin."