A shot in the dark

How do you find something you can’t see?

Elusive and mysterious, it roams our galaxies. It emits no light. It cannot be seen. It is massive, and yet it hides in plain sight. How do you search for something that seems to wish not to be found? This is the central quest that drives the Moving Universe Lab (MU Lab) at UC Berkeley. Headed by Dr. Jessica Lu, the MU Lab prides itself in coming up with innovative techniques to catch unseen black holes that wander the cosmos.

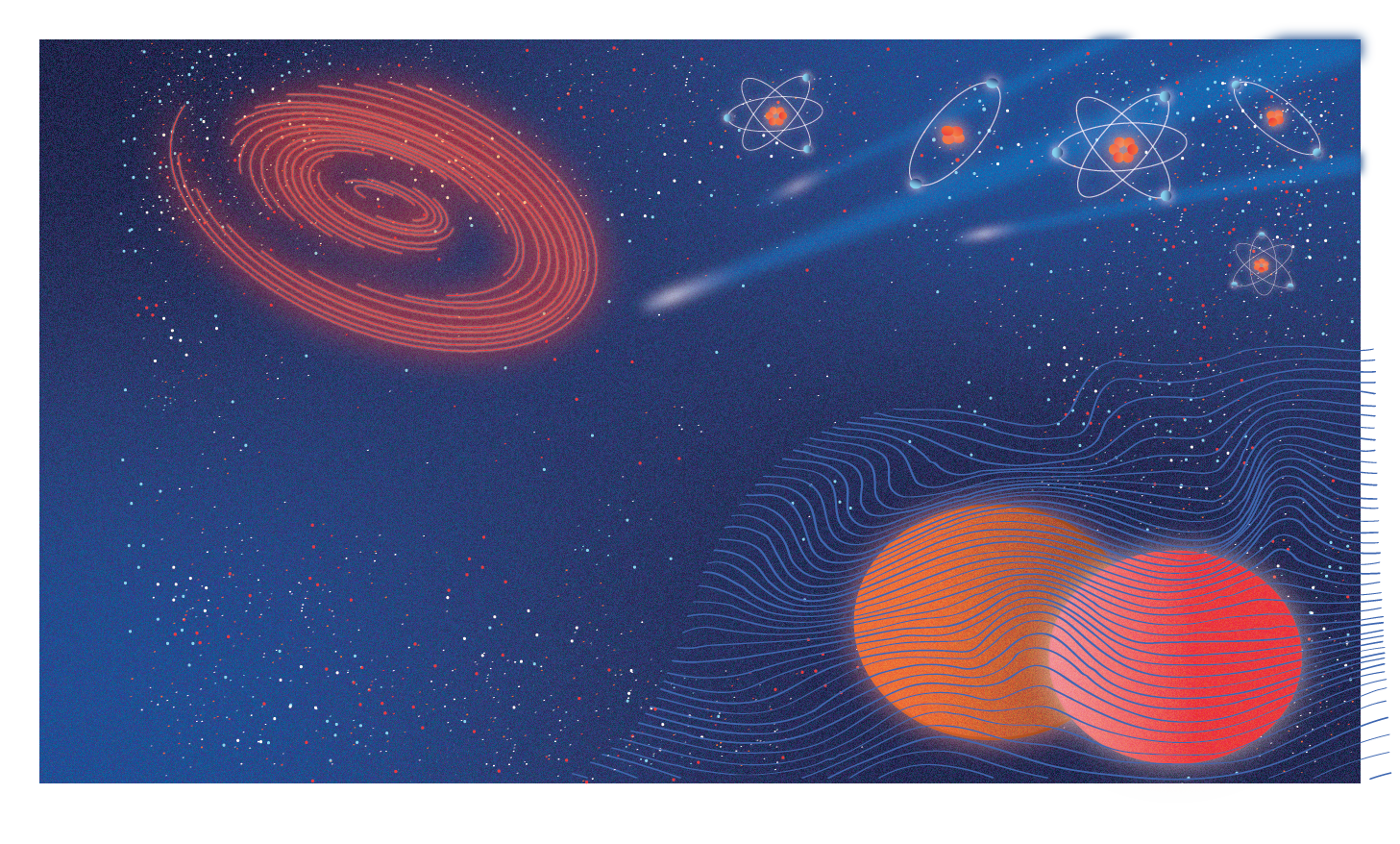

Black holes are born during impressively massive events that occur at the end of a star’s life. Sometimes, a star’s death results in a big explosion termed a supernova, shooting out a black hole at high velocity in the process. In the case of a multi-star system, when one star turns into a black hole, it breaks up the system, causing most black holes to be free-floating and isolated. Alternatively, black holes can also capture a star in their gravity, entering a new orbital pair and resulting in a binary system.

Black holes are of three major types: stellar mass black holes, intermediate mass black holes, and supermassive black holes. The stellar mass black holes have masses in the range of our sun’s mass. Supermassive black holes are true to their name and typically only found at the center of galaxies; we have one of these at the center of our Milky Way galaxy too. Galaxy mergers occasionally result in more than one supermassive black hole in the same galaxy, but ours has only one as of now.

Dr. Macy Huston, a postdoctoral researcher in the MU Lab, says, “There might be 107 to 109 stellar mass black holes in the Milky Way. We think the majority of those are isolated, with a smaller fraction being in binary systems.” Of all the types of black holes out there, free-floating black holes are especially difficult to find as they do not exist near anything, making measurements of their effects on nearby objects impossible.

So how does the MU Lab go about doing all this?

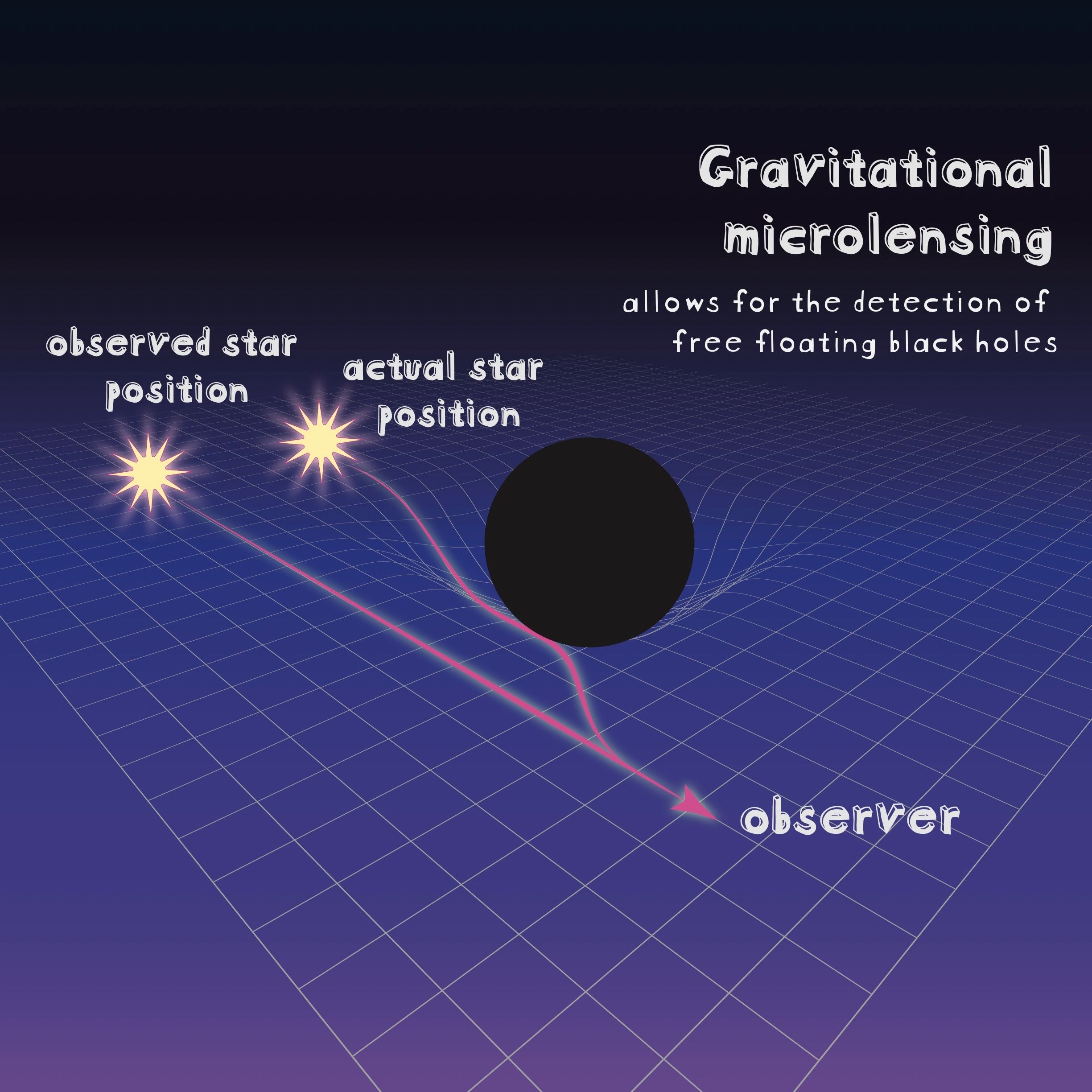

If we want to track down one of these free-floating stellar mass black holes, one can imagine how hard a feat that would be. To begin with, it emits no light, making it undetectable to the eye. We also cannot rely on detecting its presence by observing its gravitational influence on a nearby star or gas cloud because it is free-floating (and not in a binary system) and, for all we know, might be currently traversing a part of the universe with absolutely nothing nearby. This is where the MU Lab brings in an innovative trick—gravitational microlensing.

Gravitational microlensing can be used to detect even free-floating masses because, when a free-floating mass passes in front of an object, it distorts both its position and brightness slightly. Telescopes can measure these tiny shifts and pinpoint the precise locations of black holes. The MU Lab has left quite the legacy in free-floating stellar mass black hole tracking; in 2022, Casey Lam, a graduate student in Dr. Lu’s group, made the very first detection of a stellar mass free-floating black hole using gravitational microlensing.

Building their own space-based telescopes

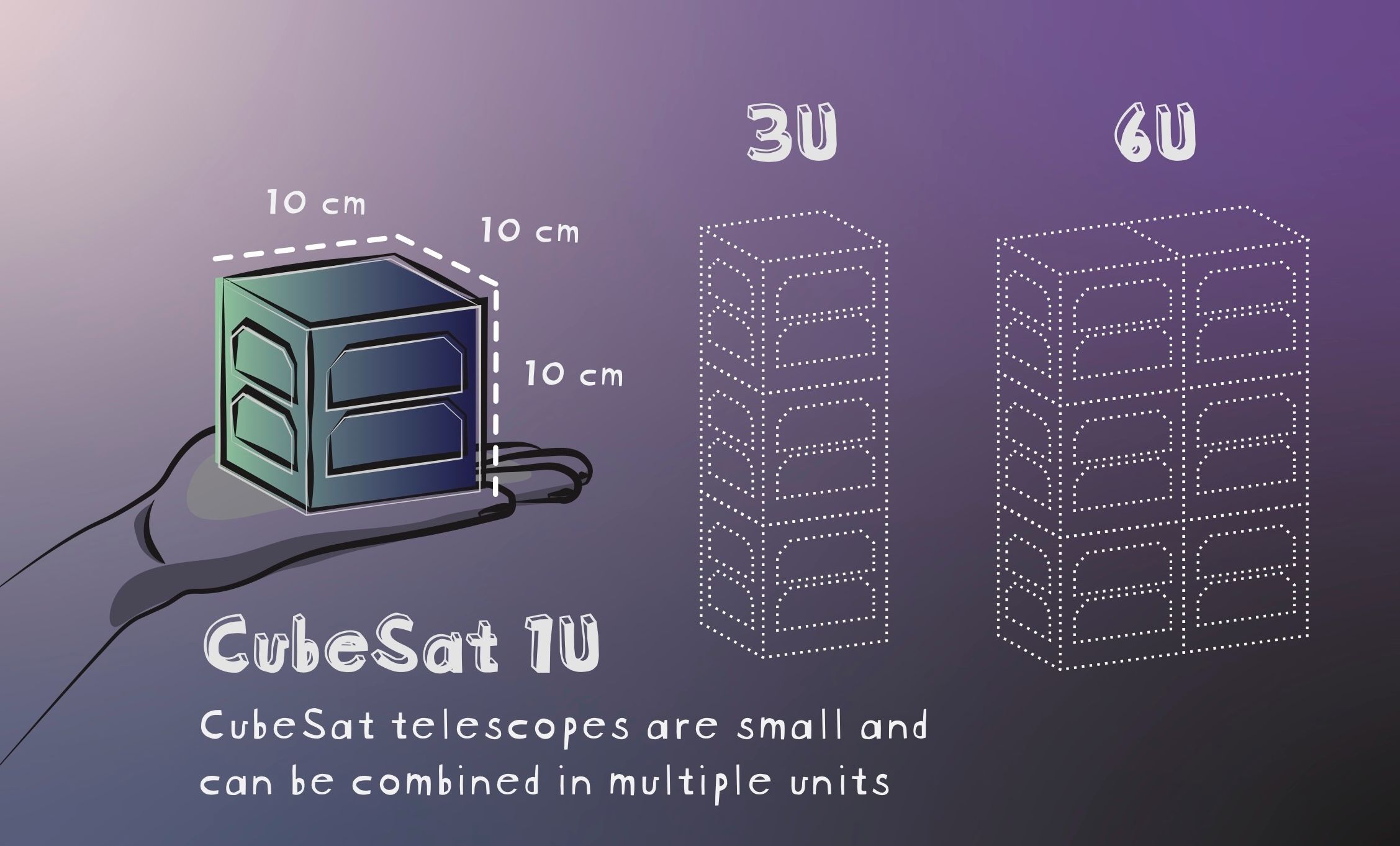

In addition to working with ground-based telescopes, the MU Lab also has an instrumentation group that builds small satellites fitted with telescopes that are launched into space. Hannah Gulick, a graduate student in the MU Lab, says that to find more black holes with microlensing, “We need telescopes to find really, really small changes in the light and take images over years. But we don’t have telescopes good at both of these.” To address this, Gulick is working on building a constellation of cubesats. These small satellites measure just ten cubic centimeters (roughly the size of a tissue box) and can be stacked together in different configurations before being launched into Low Earth Orbit 550 kilometers above the surface of the Earth. They are currently building in-house telescope cameras and testing their launch readiness and space survivability in the face of intense heat, vibration, and radiation.

The right to a dark sky and sustainability in space

The lab also prioritizes social responsibility in their research designs. Gulick says, “There are a lot of satellite constellations in the sky like SpaceX and Amazon’s OneWeb. We thus want to focus on sustainability by making our constellation small and less populated.” Gulick is also passionate about ensuring her work aligns with protecting everyone’s right to clear and dark skies. She says, “You should have access to places where the sky is dark. Outer space has meant so much to cultures and civilizations—it’s wrong to take it away.”

Black holes are ancient inhabitants of an equally ancient universe. Humans, as the new kids on the block, have chanced upon a magical key of sorts, in the form of gravitational microlensing, to catch glimpses of these ancient wanderers. As the MU Lab continues to perfect this key, let us hope to one day become acquainted with many more of these mysterious entities roaming our skies.

Correction: A previous version of this article misquoted the number of stellar mass black holes as 107 to 109 rather than 107 to 109

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.