The stories that serve the science

The real scientific process is more human than you think

A geological odyssey and an audience along for the ride

I first met Paul Steinhardt, Princeton University’s Albert Einstein Professor in Science, at a cramped breakfast table while my hair was still wet. In the cafeteria of the University of Southern New Hampshire, an overly polite yet increasingly agitated crowd had just formed around the coffee carafes, as 70 or so scientists all tried to squeeze in one extra cup. It was minutes before the first talk of a small research conference, and surely almost everyone in the room was dreading the freakish heatwave of 98°F with 100 percent humidity that waited for them outside. But Dr. Steinhardt was smiling nonetheless when I grabbed the seat across from him.

I knew who he was as soon as I sat down. With a ring of graying hair, a somewhat ill-fitting checkered dress shirt, and a blunt but reserved demeanor, he was the exact image of the physicist that gets a few minutes of screen time in any classic apocalyptic blockbuster. Having seen his work come up repeatedly during my PhD, I wanted to ask him a hundred questions, but I tried to play it cool. We and some other graduate students mostly chatted about where we were from and complained about the weather until it was time to head to the talk.

For the next week, Dr. Steinhardt sat in the front row of every presentation. He would have been an intimidating scientific figure to most of the speakers if not for the relaxed, avuncular vibe he exuded. By the end of the conference, you could see the fatigue on the faces of every audience member, worn down by both the heat and the sheer volume of information that had been thrown at them. For an inexplicable reason, the final talk of the conference was scheduled for 8:30 p.m. I almost left early, but it was going to be given by Dr. Steinhardt, and something told me I didn’t want to miss it. I was right about that.

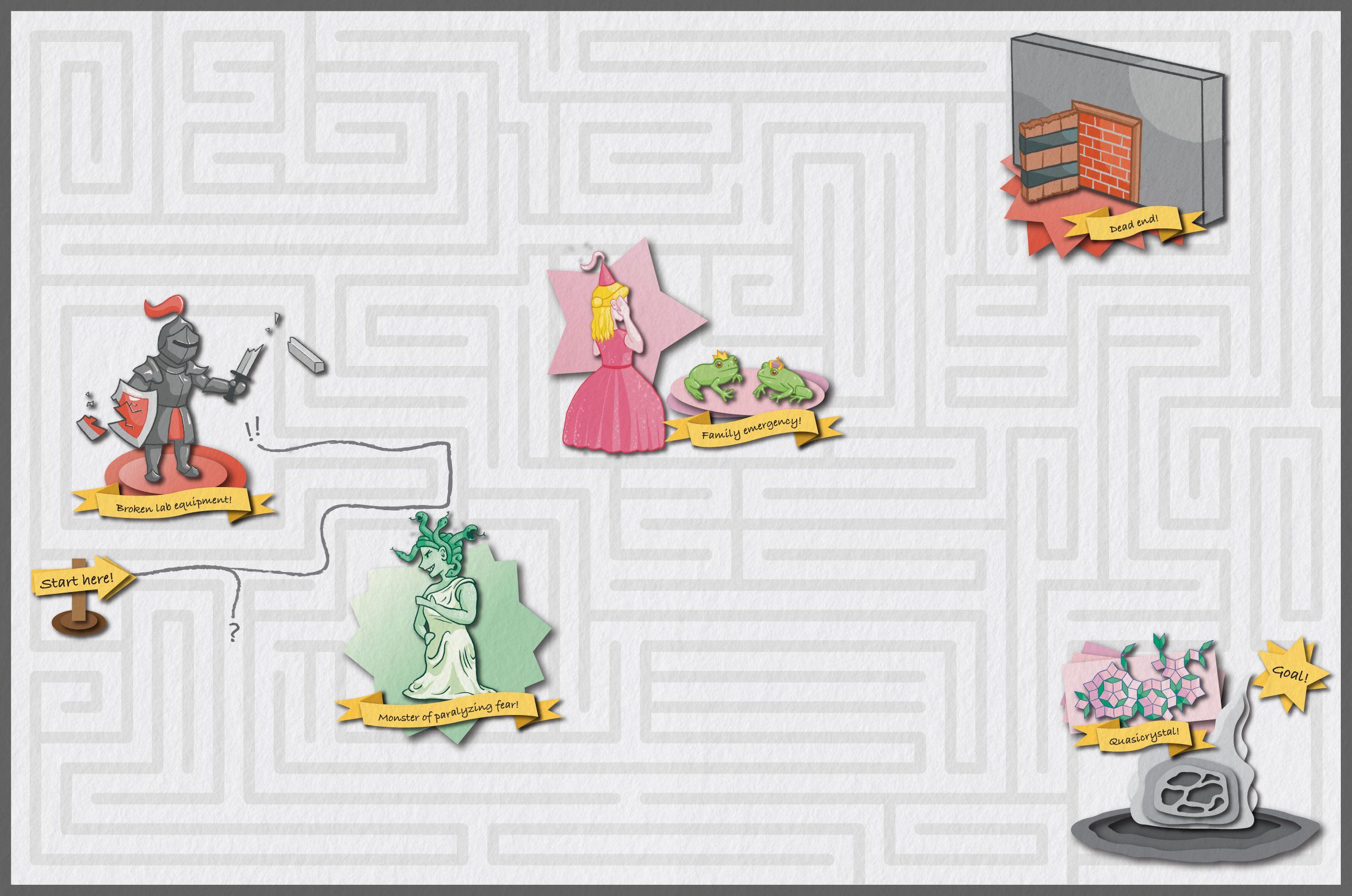

Dr. Steinhardt told us the story of the first naturally formed quasicrystals, a type of material many people thought impossible before he and his colleagues theorized them. To understand how cool that is, you’ll need to know that crystals are solids where the positions of the atoms form a repeating pattern. To make the simplest type of crystal, you can picture a piece of graph paper and imagine placing an atom everywhere that two lines cross. Quasicrystals are also solids where the positions of atoms form a pattern, but the key difference is that the pattern never repeats. It is not periodic, as a scientist would say.

As an example, imagine that instead of arranging a bunch of squares on a piece graph paper, you used pentagons. You could still make a nice pattern with the pentagons, but it turns out that if that pattern is symmetric, specifically if it has the same five-fold symmetry that the pentagons themselves do, the pattern cannot be periodic. Just because of the geometry of the pentagon, the pattern can’t repeat. If you wanted to continue the pattern you made initially, you’ll always need a bigger piece of paper. Unlike with the square graph paper, there will never be a point at which you can just make a copy of the page you have and stitch the two together.

In a sense, because of this symmetric but nonrepetitive structure, quasicrystals break the “rules” of physics. If you were to shoot a beam of particles at them—every physicist’s favorite experiment—the particles would scatter off and form a signal in your detector that is literally referred to by scientists as “forbidden.” Even after these strange materials were made in the laboratory, many people believed they could never be formed without the aid of a human. Dr. Steinhardt and a team of collaborators believed that they could be formed in super high-pressure collisions like those that occurred between asteroids when our solar system was first coming together. A team of intrepid geologists, alongside the bookish yet determined Dr. Steinhardt, trekked deep into the wilderness of eastern Russia to find the remnants of the four-billion-year-old asteroid that eventually proved this idea true.

I’m not even doing the story justice. The twists and turns, dead-ends and frustrations, confusion and mistakes of the quasicrystal tale are all vivid when Dr. Steinhardt tells it. The most interesting part of the talk to me, though, was the reaction of the audience. At the end of any other weeklong conference, attendees would clamber to get through the doors once the final talk concluded, but as I surveyed the room, it seemed like most people would have been content to listen to Dr. Steinhardt for another hour. Many did stay to talk with him long into the night. And months after that presentation, I still remember it. I remember the entertaining anecdotes and the scientific content, too, but mostly I remember the way he told the story. He chose to talk about science in a way that was completely out of the norm for the setting of an academic conference, but in some ways it was the most effective talk I heard that week. And since then, there has been a question bouncing around in my head: Are the ways that scientists communicate serving science best?

The wrong kind of scientific story

A few weeks after the conference concluded, I called up Dr. Steinhardt to help answer my question. A part of me still wanted to ask him a hundred questions about his work, but again I managed to restrain myself. Instead, I listened to him explain how his personal philosophy of science was formed. Dr. Steinhardt wanted to be a scientist ever since he was three. But when he set out as a child to learn about the famous scientists of the past, he found their stories lacking. He told me that the accounts he read of great scientists or great scientific theories “seemed to go from victory to victory, without any hint of struggle.” Even without direct experience in the scientific world, this straight-line path struck the young Steinhardt as distinctly uninspiring. When he became a scientist, he realized that it was also completely untrue. Just as he presents in his quasicrystal tale, Dr. Steinhardt knows that real scientific progress is not even close to a linear progression of experiments, results, and theories. Science is a winding, rocky trail that loops back on itself 10 times before—in some cases—helping us understand something new about our world. To Dr. Steinhardt, it is a true disservice to cherry-pick the triumphs in any scientific story because “the reality is always more interesting than the fairytale.”

As we discussed the messy nature of the real scientific method, it made me think of the first time I met Dr. Dione Rossiter, the executive director of UC Berkeley’s scientific community outreach office, Science at Cal. She was giving a presentation on career opportunities outside of the usual academic track for a group of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, but she opened the presentation by telling her own story. She talked about pursuing physics when she was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley. She talked about counting the number of other women of color in each classroom or laboratory she stepped into, and often stopping only at one. She talked about several times when she wanted to give up and drop out. But she didn’t give up. During her PhD, she developed a passion for using science as a means to engage with a broader community. She realized that the way science was usually communicated to the public simply didn’t work, and she devoted the rest of her career to trying to change that.

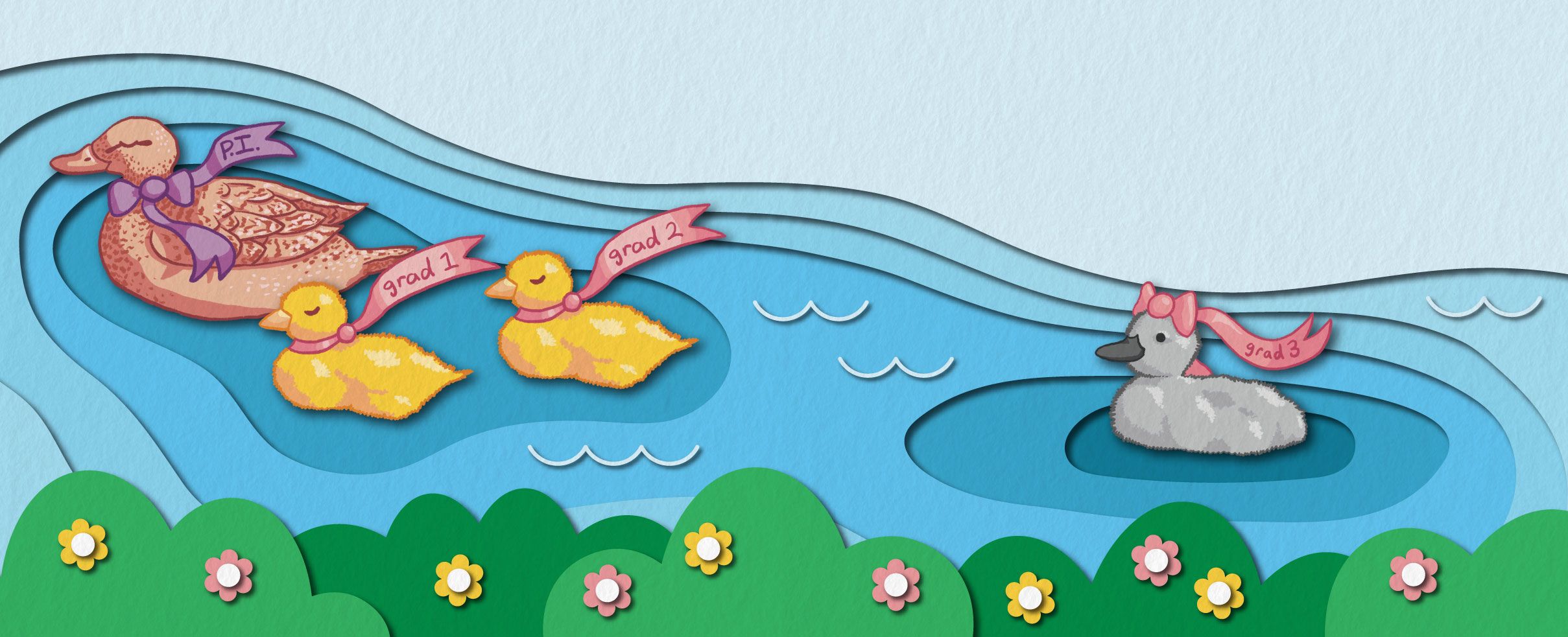

Dr. Rossiter emphasizes that the “fairytale” of the scientific process that Dr. Steinhardt describes not only paints an inaccurate picture for the public but also limits the accessibility of academia for young researchers. She points out that the mindset that science is purely objective forces scientists to hide or sacrifice pieces of their humanity when they enter the lab. Inevitably, this leads not to some haven of intellectual thought devoid of subjectivity, but rather to a space that defaults to a single, dominant culture. She argues, “Some scientists will say they don’t care about who you are and what your cultural background is, because when you go into the lab, that doesn’t matter. But that’s a lie. There’s only one culture there and that does matter.”

This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the “fallacy of objectivity.” That is the mistaken belief that scientific programs are nothing but logical, from the conception of the experiment through the analysis. Any scientist would agree that scientific inquiry is based on data, and data should be acquired and analyzed in a way that is as objective as possible, but those who reject the fallacy of objectivity understand that it will inevitably still matter who is doing the science. The questions that are asked, the methods used to investigate them, and the conclusions drawn will all be informed consciously or unconsciously by the experiences, biases, and perspectives of the people in the lab.

Dr. Steinhardt knows as well how scientists—in the quest for a level of objectivity that will never be obtained—can sometimes craft stories of a flawless scientific process that never was. In the 1980s and 90s, for example, Dr. Steinhardt contributed quite a lot to a theory called “cosmic inflation,” which describes how the universe may have expanded in the moments following the Big Bang. Today, however, he is one of its most vocal opponents. I won’t dive into the inflation argument itself, but Steinhardt’s reversal does demonstrate a commitment to scientific integrity, underscoring that scientists are human and carry personal biases. Dr. Steinhardt explained that when you invest a lot of time in a theory, “You can overlook its flaws. Or you can convince yourself you have addressed the flaws when you haven’t … Admitting you made a mistake 25 years ago can be a very hard thing to do.”

What kind of scientist would you trust?

Like anyone else, scientists have an image of themselves: a story they write—consciously or not—about who they are and what it means to be a scientist. And this story inevitably affects both the way science is done and who feels a part of the scientific community. After talking to Dr. Steinhardt and Dr. Rossiter, I wanted to speak with someone who has intentionally used their story to expand the set of people who feel like they belong in science. Really, only one person came to mind.

Dr. André Isaacs is a tenured professor of organic chemistry at the College of the Holy Cross, and he would probably be most recognizable in his iconic pair of black and red high-heeled boots, dancing to Beyoncé or Nicki Minaj. He has hundreds of thousands of followers on TikTok and often posts videos alongside his students, performing the latest trending dances and pulling off outfits that most other chemistry professors could only dream about.

Born in Jamaica and an openly gay man, Dr. Isaacs’ personal story is an uncommon one to find in the physical sciences at an academic institution in the United States. Early in our conversation, he fondly recalled the science lessons his uncle taught him when he was a teen. This personal influence and his uncle’s unique ability to connect scientific topics with everyday life is one of the main reasons Dr. Isaacs ultimately pursued a career in science. Today, while most of his time is still spent on rigorous academic research and teaching, Dr. Isaacs makes time to engage with a huge community online. He creates his short video content in part because he honestly does love to dance, but, more importantly, he feels that sharing his full humanity is the best way to connect to his students and train young scientists. He told me, “Embracing content creation was my way of showing to my Gen Z students that I’m embracing their culture … [When they join my lab], they think, ‘This is a place where I can be myself. This is a place where I can thrive.’” In Dr. Isaacs’ view, setting the expectation that one’s full identity is welcome in the laboratory not only attracts new students to research, but also allows for a richer and more effective mentorship experience. He says simply, “Having more things in common builds trust. It makes conversations easier, about chemistry and beyond.”

Of course, students are not the only people with whom academics need to build trust. In a time when all aspects of scientific research and the academic mission are being attacked and defunded, scientists are forced to find a way to fight back. For many scientific organizations, fighting back means directly lobbying the politicians who want to cancel research funding. But in the long term, a sustainable system of publicly funded research requires convincing the public that research has value. Enough value that it’s worth fighting for.

In our conversation, Dr. Isaacs tied the decreasing trend in science literacy to the lack of trust in science within the United States. He told me he thinks people who aren’t exposed to the ways that science can directly impact their lives tend to “see scientists as gatekeepers.” He was also quick to point out that the most effective strategy to improve science literacy in a permanent way would be to fund science education in our K-12 public schools on the level it deserves. Still, he emphasized that all scientists can play some kind of role in breaking down barriers between academia and the public. And those roles will likely be highly individual. Certainly not everyone will be as comfortable in front of the camera as Dr. Isaacs is, but based on the feedback he has received from the scientific community, he feels that “lots of folks are realizing the power of being authentic … and that it can have a massive impact, even just on the graduate students they mentor or the students in their class if they bring a piece of their authentic selves.”

Find your audience

To round out my sense of what a scientist who takes communication seriously might look like, I spoke to one last professor: Sean Carroll. While Dr. Isaacs is the scientific maestro of short-form content, Dr. Carroll, a professor of natural philosophy at Johns Hopkins University, has found success in long-form media. He is the author of six popular-level books (so far) and the host of a weekly science podcast called Mindscape. Unlike Dr. Isaacs’ emphasis on personal connection, Dr. Carroll tends to dive deep into big, philosophical ideas, both with the academic guests on his podcast and in his own writing. Yet, the message I got from my conversations with these two contrasting communicators was mostly the same. It was that the most important thing a scientist can do to communicate more effectively is to accept that communication is not simple. It requires serious thought, and the strategies will change drastically based on the context and the audience.

In a classic physicist way, Dr. Carroll used the phrase “nontrivially difficult” to describe science communication. But he went on to say simply that, “Science communication is a skill, a skill that you have to develop, and I think you have to develop it by doing it … by talking to different audiences and asking them for feedback on what’s working.” Dr. Carroll is someone who has put in the effort to convey big ideas effectively to a variety of audiences throughout a long and successful academic career. But even he, toward the end of our conversation, admitted, “I have no grand plan for making [science communication] better.”

Perhaps the way forward, then, is just for more scientists to accept the fact that communication will inevitably be a part of their job. Dr. Steinhardt didn’t just restate the topline results of his papers when he gave the talk I attended. He tried to teach the audience something new in a way that makes them understand and makes them care. Dr. Rossiter didn’t give up when she felt like she had to leave her identity at the laboratory door. Now she helps scientists showcase their work and share their passion in a way that feels not like a lecture but an invitation. Dr. Isaacs doesn’t adhere to the false notion that scientists are inanimate vehicles for a “scientific process” that’s disconnected from themselves. He embraces and showcases his full personhood for thousands of people to see, with the knowledge that there are those that will come across his joy and feel like they belong in the world he calls home.

Most scientists will never communicate on the scale of Dr. Isaacs or Dr. Carroll, but they all will have students, mentees, friends, and family. They all will write papers, give talks, and craft grant proposals. So maybe the way to best serve science is just to ask oneself, am I best serving my current audience? If the answer is no, assess the flaws, seek feedback, and try the experiment again just like any good scientist would.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.