Investigation without exploitation

Incorporating indigenous worldviews into academic science

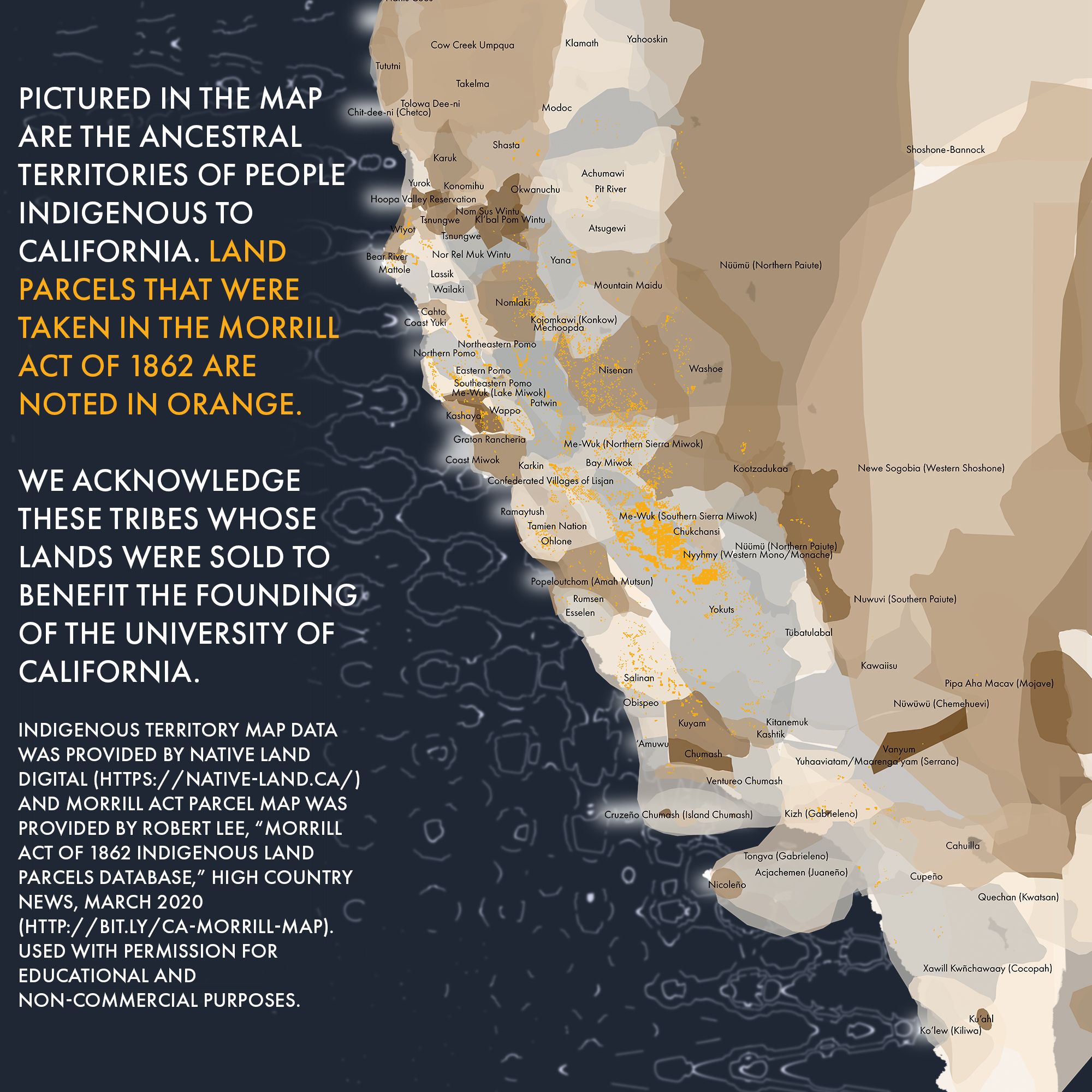

If you’re reading this article, you’re likely one of the more than 56 thousand students, faculty, and staff at UC Berkeley benefiting from stolen land. The Morrill Act of 1862 granted 150 thousand acres of Indigenous land—spanning 122 tribes—to the state of California to establish universities. Therefore, we must acknowledge that the building you’re likely reading this in sits on the territory of xučyun (Huichin), the ancestral and unceded land of the Chochenyo speaking Ohlone people, the successors of the sovereign Verona Band of Alameda County. This land was and continues to be of great importance to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and other familial descendants of the Verona Band.

The land on which UC Berkeley (and the entire UC system) resides is not the only way academia and science have taken from and harmed Indigenous peoples. Countless times, DNA and blood samples have been used for research that Indigenous communities did not consent to. And UC Berkeley still has yet to return all of its over 167 thousand funerary objects and 11,900 remains stolen from Native American graves—some of which have been used for teaching or research purposes—with only 71 percent and 60 percent, respectively, made available for return as of January 2025.

Our society’s dismissal of Indigenous knowledge has also harmed us. For those of us in California, one of the most apparent examples is wildfires. Forest fires are a natural part of ecosystems important for the life cycles of forests. Indigenous people have used cultural burns as stewardship of the land for thousands of years, until settlers prevented them—going so far as to pass a law banning intentional burns in California in 1850. The law led to the out-of-control wildfire landscapes we’ve seen, as underbrush grows denser, providing kindling for large forest fires that burn hotter than the ecosystem can tolerate. Recently, we’ve seen research demonstrating the value of controlled burns (we’ve even featured some of this research in Issue 43). Even Smokey Bear has caught up with the knowledge, changing the “preventing forest fires” slogan to “preventing wildfires.” Meanwhile, local Indigenous communities have been promoting this stewardship all along.

Efforts are finally being made to bridge the gap between Indigenous communities and Western academic research. Several UC Berkeley researchers have been working hard to repair harms by getting Indigenous communities involved with research and creating an ethical and circular bioeconomy (closing the loop between biotechnology and biodiversity and the Indigenous communities who steward it), integrating Indigenous science with Western science, and ensuring that the benefits of the academic research developed from this knowledge are given back to these communities.

Lessons from Indigenous knowledge

Dr. Andrea Gomez is one of these researchers integrating lessons from Indigenous knowledge with her research. A neurobiologist and assistant professor in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Gomez focuses on neural plasticity and the molecular mechanisms that balance the stability needed for memory retention and the flexibility needed to learn. Gomez approaches this through studying RNA, the molecule that transmits DNA information into cellular outcomes. She’s interested in how regulation at the RNA level translates into the assembly and maintenance of neural circuits. Gomez says, “I’m not a DNA hater, but the fact that you can create so many different structures of RNA that have function and also encode information at the same time I think is really fascinating.”

And it is, but—like with many new discoveries in science—the alternative RNA splicing field was once heavily overlooked. Alternative RNA splicing is the process that allows one gene to code many different proteins by making multiple different mRNA transcripts. “For a long time, people in the splicing field were like, ‘RNA is just noise. Alternative RNA splicing is just noise,’” Gomez says. “I think noise is very valuable because noise creates an opportunity; it creates the possibility for adaptation.”

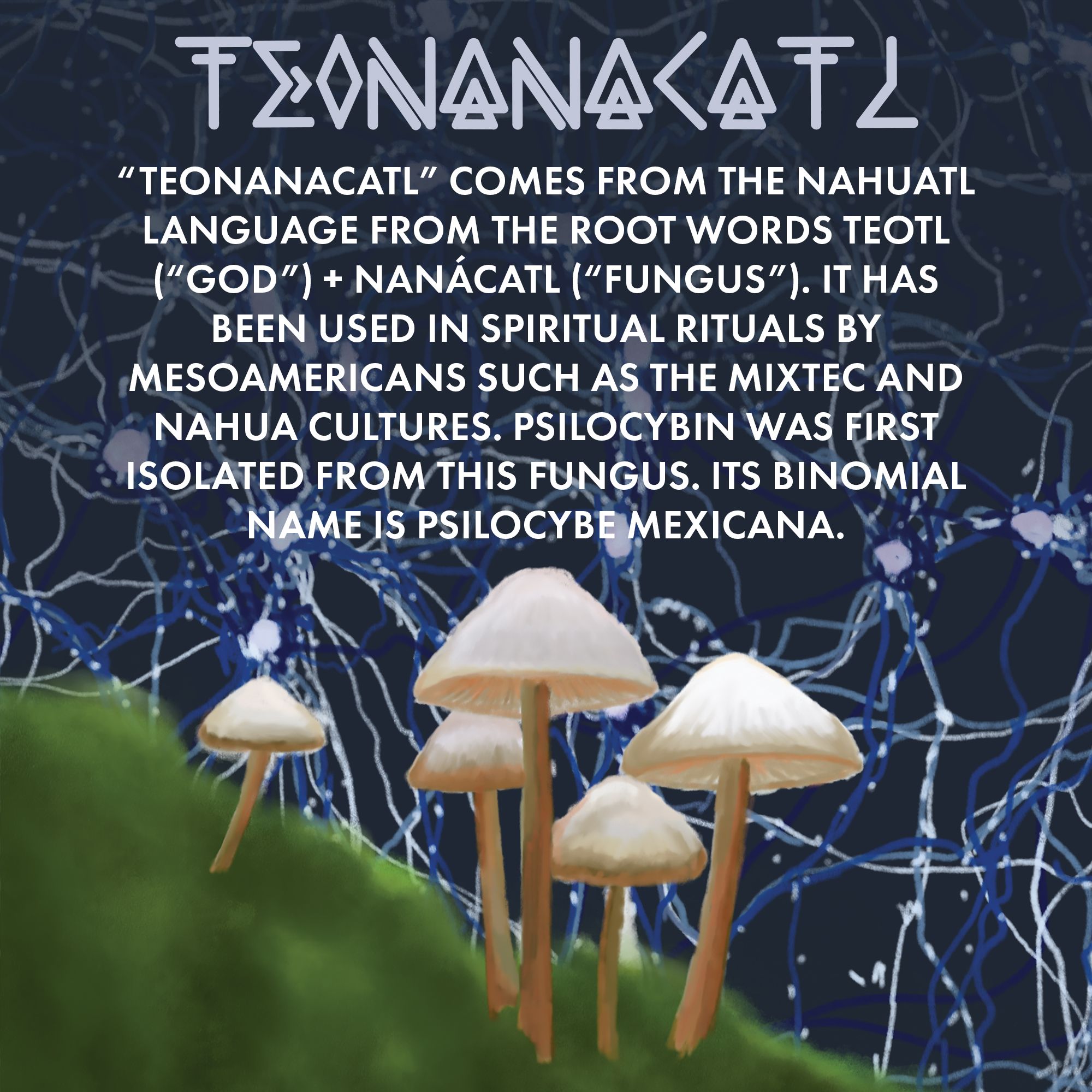

Gomez utilizes alternative RNA splicing within the rapidly expanding field of psychedelics research to gain insight into the mechanisms that open windows of plasticity, which led to Gomez’s synthesis of Western and Indigenous value systems. “For me, there was a clear difference in the way that we are using psychedelics in a Western context versus how psychedelics are used in Indigenous contexts from the perspective of medicine,” Gomez says. “Outside of the clinical session, the features of an individual’s life are not necessarily considered. Where, in the Indigenous perspective, everything about the individual is not isolated, you consider all their relations.”

This context can have a large impact on the measurements that are taken and the questions that can be answered. Considering the whole individual can expand what we’re even looking for while testing people and model systems. “What types of things do you expect a mouse to do differently after a psychedelic experience? How can that model a human pathology?” Gomez asks, acknowledging that you can’t exactly set a mouse in front of a screen and see how a drug will change that behavior, because mice—while being a great model with a prefrontal cortex—live very different lives from people. But like people, mice also have their own predispositions, and that can impact one mouse’s response to a psychedelic versus another’s response.

“I consider and read as much as I can about different value systems and epistemologies,” Gomez says. “How we are creating knowledge, really questioning how we’re asking questions and the value systems in which we’re asking these questions.” Indigenous knowledge taught Gomez to consider the whole, and she notes limitations in the Western perspective, pointing out how commonly only serotonin receptors are considered when investigating psychedelics, while these compounds can bind to numerous receptors, for example. When we box ourselves into one value system, we can only study what our limited tools allow and only ask the questions our limited experience opens us up to.

Gomez acknowledges that “sometimes it’s really hard to synthesize two different value systems,” but if there’s anything my conversation with Gomez taught me, it’s that there’s so much potential in doing so. Considering the whole (whether that be an entire individual or a molecular system), expanding our toolbox, and questioning our questions allows us to identify the gaps in research. Is there something we’re missing or not taking into account? Is there another angle from which we need to look at this problem? How have our Western science perspectives limited our research questions, or the questions we can even ask? Once we reckon with these questions, the benefit of integrating value systems becomes clear.

An open conversation with Indigenous communities

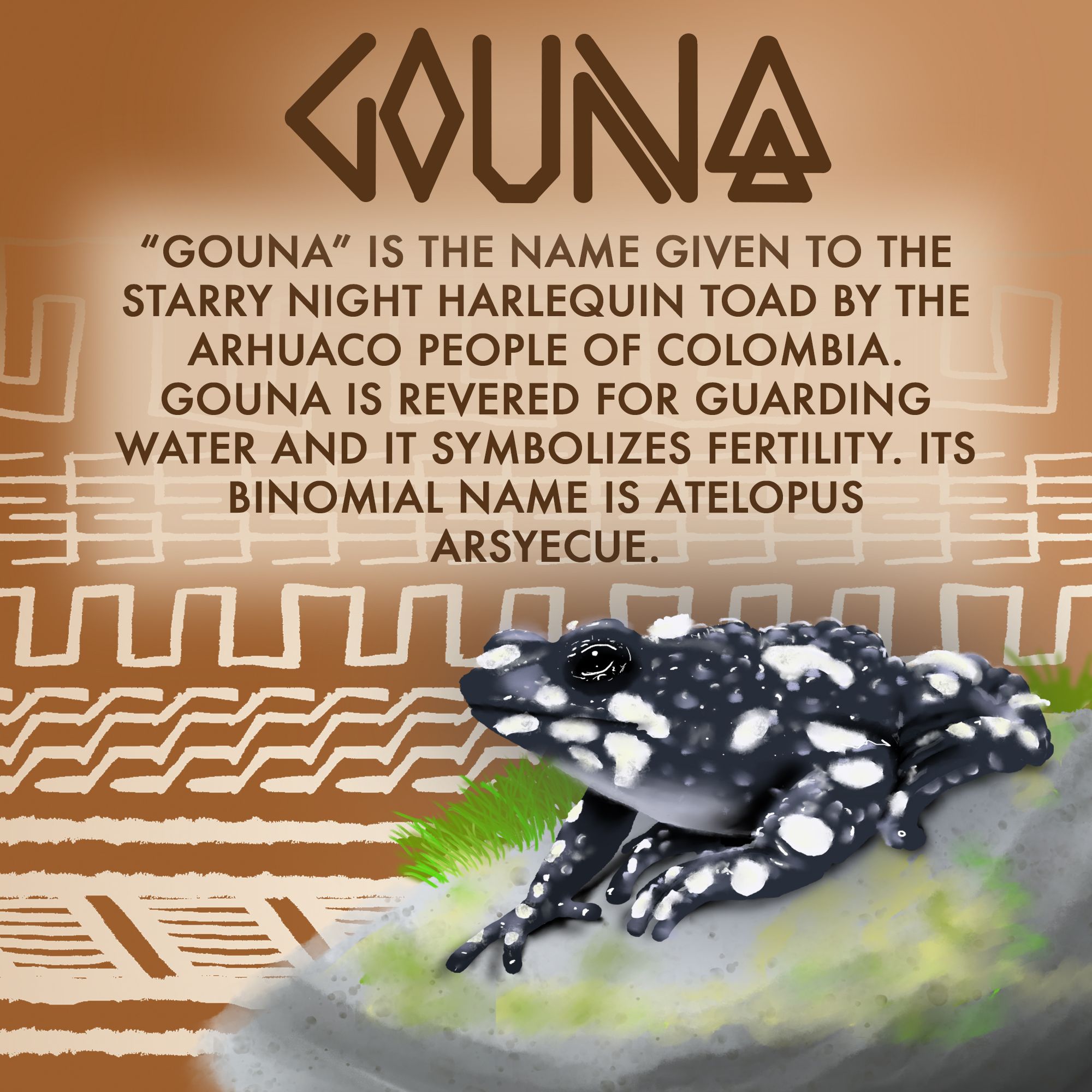

The consideration of others’ value systems doesn’t stop at our research questions. Majo Navarrete, a PhD candidate in integrative biology, discussed her incredible research studying the evolution of chemical defenses, or toxins, in frogs while working alongside local Indigenous communities. Since many diverse animals produce the same toxin, researchers correctly assumed that the shared toxin came from an external source. Navarrete is studying that source in frogs: a symbiotic association with bacteria. This has led her to conduct fieldwork in Ecuador and Colombia, where she’s worked closely with local researchers and communities to approach her research questions in a thoughtful and responsible way. “It’s important that the way that we approach nature incorporates the people as well,” Navarrete says, “because they have needs, and they’re going to be affected by whatever our work says.”

There are many benefits to having an open dialogue with local communities. “The way we understand science in academia is a narrow perspective of the world,” Navarrete acknowledges. “It’s coming from a certain group of people, historically white men. And the perspectives that they have, as valid as they are, are also very limited. I think it’s important to collaborate with people that see and understand the world in a different way, and who have been interacting with these animals and the ecosystems for longer than we have.” This can lead to more well-rounded research questions, as well as safer expeditions. Navarrete’s team hires a local guide not only to give back to the local economy, but also to learn how to maneuver through the environment safely.

“It’s not about just incorporating the views,” Navarrete points out, “but also having the people participate in the process and giving them the credit, being collaborative.” Unfortunately, ecological practices in Western science have been historically colonial, stealing discoveries from Indigenous communities and framing it as though the scientist discovered it alone, which is why bringing collaboration into research is so important. And there is no “one-size-fits-all” method for collaboration. As Navarrete mentions, it takes careful consideration: “It’s very case dependent, and that’s why it’s important that people take this very seriously because it requires a lot of compromise to understand the specific political situation of a certain Indigenous community, the history of that community, and how it has interacted with the government and with other researchers.” And it’s not all external work either: “There is also personal work that has to happen, so someone has to reflect on their own biases.”

However, researchers don’t need to start from scratch. Navarrete’s first step when planning to do fieldwork in a new community is establishing a collaboration with local researchers, including social scientists who’ve been working with these communities. As Navarrete pointed out, it’s weird to just show up at someone’s house expecting them to collaborate with and trust you, so local researchers can be crucial to facilitating conversations. “The very basic guidelines,” Navarrate says, “are being respectful, open, communicative, and honest. Certain things that are very basic to any human interaction can be translated to establishing proper collaboration with Indigenous people and locals living in the community.”

Navarrete gave me an example of how important these conversations can be. While researching frogs in Colombia, Navarette learned that “some of the species that I wanted to study are considered sacred. I wouldn’t have known otherwise that they don’t allow for the collection or taking samples of any of those frogs, if I wouldn’t have started a conversation with the local researchers first.” With that knowledge, Navarrete decided not to include those species. “Sometimes we have to give up. Even though we think it’s really important for the story, I don’t think it’s worth overstepping on people’s lives and their cosmic vision of the world. The collaborative part is to accommodate our research questions based on how the people we’re working with are informing that: their boundaries, their needs, their interests.”

In another example, Navarrete told me about a community in the Andes of Ecuador, where a kid found a frog species that was thought to be extinct for about 25 years. In 2016, with the intention of helping preserve the species, researchers bought the frog. However, neglecting to explain the situation to the community, the researchers inadvertently prompted locals to begin collecting more frogs to sell, ultimately harming their goal. Recently, Navarrete helped establish the Alianza Jambato (Jambato Alliance)—founded around the jambato toad from Ecuador—where researchers from a multitude of fields work together to build a collaborative relationship with local communities to start giving back.

Navarrete took part in multiple collaborations with the community, from hiring local guides to rotating which houses the researchers stay in to evenly distribute the monetary benefits across local families. Her team presented findings at local meetings, asking questions such as: “What do you think about the research we’re doing?” “Do you have any specific questions that you’re concerned about?” and “What would you like us to incorporate in our work?” Sometimes, collecting samples from frogs leaves visible marks on them. Navarrete explained the methodology and why it’s important, informing the community about the impact the research might leave around them for a little bit. Beyond this, Navarrete’s team engaged with the community by participating in local events, holding classroom workshops with live frogs, and learning from the kids about their home. The frog became an important symbol and even tourist attraction to the town, which is the last refuge for this frog. Navarrete admits that she usually can’t put this much dedication into a collaboration but emphasizes that she always follows the basic rules of asking for permission, hiring local guides, and treating the local community with respect.

My conversation with Navarrete ended with an important lesson for everyone to keep in mind, especially those doing fieldwork outside of their country and community. “It’s important to accept the fact that there is always going to be a power dynamic and a colonial component and living with that uncomfortable feeling and uncomfortable fact that it’s not 100 percent okay,” Navarrete says. “Because if things were fair, an Indigenous person from Ecuador could say, ‘I want to go study salamanders in the US.’ It could be symmetrical, but the relationship is not. Just accepting the fact that it is how it is and trying to improve the practices from there is a more honest approach than saying, ‘I’ve never done anything wrong.’” As Navarrete says, “It’s important to accept that there is a power dynamic and think about what to do from a more honest place.”

Creating an ethical and circular bioeconomy with stewards of the land

You might be thinking this is irrelevant to you, that your research is has no connection to Indigenous groups, but you might be surprised. Maria Astolfi, a synthetic biology PhD candidate in the Keasling Lab, describes when she realized that her research might have some unethical origins: “When we are working on projects that are ambitious and have been developed for a while, you see that the project may not have an ethical relationship with the community. Those are the types of projects I work on in the United States. The ship was going when I joined the project, and I suddenly was like, ‘I think what’s being done here is wrong.’”

Astolfi uses “synthetic biology to protect biodiversity and Indigenous peoples and local communities.” A descendant of the Kambeba/Omágua tribe and born and raised in the Amazonian rainforest, Astolfi co-founded the first SynBio Lab there in 2013, whose main goal was bringing advanced technology to the rainforest for environmental challenges. The lab focused on developing collaborative solutions to problems identified by local communities. “In the Amazon, we worked on local solutions for local problems,” Astolfi says, pointing out that research on local problems is common in Brazil. Her lab worked on developing a solution for heavy metal contamination in Amazonian rivers, a problem that impacts biodiversity and human health.

After coming to the United States to do biotech research, Astolfi was surprised to find that locally focused research was not the norm. Instead, US researchers were focused on solving global problems, including those in regions the researchers may have never visited. “That was the moment I realized that what I did back home was rare,” Astolfi says. She wanted to bring the model of research she did in the Amazon to her research in the United States. “We felt like we had to do the public engagement in the beginning, not the end.”

This globally focused research was not the only difference, either. The United States is not a signatory to the Nagoya Protocol by the UN Convention of Biological Diversity, which provides a legal framework for fair and equitable benefit sharing with Indigenous communities. So Astolfi found herself in an unfortunately common situation in the United States: “Working on synthetic biology in the United States, it is normalized to take [genetic] data from the Global South and patent that information for profit, with no ethical collaboration or benefit sharing strategy with the countries where these samples originated, because it’s not required in the United States. In Brazil and in many countries, this is highly regulated [through the United Nations’ Nagoya Protocol].” The lack of collaboration and benefit sharing didn’t sit right with Astolfi.

Often the only international student and woman in the room, “It took courage to propose other ways to do science in well-established places,” Astolfi says. “There’s that moment of realizing, ‘I think we should be doing something different than what’s been done right now. How can I talk with the leaders in a way where they will feel empowered to do something about it, in a practical way?’”

This was no easy task. “So, there’s this thing that I think is wrong, and I need to mobilize people to work towards doing better,” Astolfi describes. “It ended up being a lot of learning how to talk about these ideas in a way that makes people feel empowered and not guilty.” This can be an incredibly stressful task, especially if you’re the only supportive voice in the room. Astolfi made clear the importance of finding your community: be the one voice in the room when you need to be, but make sure you have your community’s support and mentorship to fall back on.

It eventually comes down to creating conversations for Global North scientists and Global South communities to understand what benefits each group. “My work is making bridges between the two communities,” Astolfi says, “raising awareness for the communities on what we are doing in the lab, while raising awareness for people in the lab on what the communities have done for centuries. It’s facilitating the meeting of these two worlds and finding beneficial agreements for both.”

Despite the stress of the work, there are a lot of positives, too. Astolfi has gotten to meet many people and hear their stories. On the Ak Chin Indigenous reservation in Arizona by invitation of Arizona State University’s Professor Krystal Tsosie (Diné/Navajo Nation), she was welcomed into a community where “there was an elder and activist, Ofelia Rivas (Tohono O’odham Nation), telling stories of the land and her relationship to the desert and their ceremonies. I started crying because it was so emotional, her people have been fighting for so long.” Astolfi describes getting to spend time with these communities and hear them speak about their relationship with the land: “It’s just so beautiful and invigorating and energizing.”

However, communities have had far more struggles than their knowledge being stolen. “When we’re talking in biotech,” Astolfi explains, “my work is giving back ownership of traditional knowledge and Indigenous science, but many groups are fighting for land or for drinking water.” Astolfi points out the power that benefit sharing in biotech can have, citing work by Professor Keolu Fox at UC San Diego and a pioneering deal with the start-up Variant Bio and Novo Nordisk. “That money is going back to the community to build the first hospital in the community [in Tahiti (French Polynesia)].” Astolfi explains that biotech can be a tool for helping Indigenous communities take back their rights. “There’s biotech and what we do in the lab, and there are the basic rights that need to be met for Indigenous groups, and hopefully we can leverage biotech to then fund these basic needs. What we want to do is get land back, so how can biotech be a tool for land demarcation and Indigenous self-determination?”

Giving back to the communities from which academic institutions and companies have profited is one step toward more equitable science, but another is allowing a community to do their own research, instead of insisting we have the answers. Ending our conversation with lessons from Amazonian research, Astolfi wants us to “question if we truly understand the problem that we are trying to solve. Research is one part of a holistic component that will lead to social change. Science and technology must communicate with policy, society, culture, people, and land.” While it may be desirable to fix global problems from the lab bench, how can we fix problems in places we’ve never been, with communities we’ve never spoken to? “I hear so many times scientists from the Global North developing something for the Global South and saying, ‘We will convince them later of the benefits of this.’” Astolfi reminds us, “There are so many problems right here that we can solve. So, getting closer to the local would transform science for the better.”

Expanding our worldviews with consent and collaboration

Throughout meeting with these incredible researchers, there’s been one major theme that’s jumped out at me: one person/lab/group/community cannot solve all the world’s problems. We are better when we work together with communities, local and abroad, and learn from those with experiences beyond our own. “We really want to believe that we are being as objective as we can be, but because we all come from different situations, there is going to be an intrinsic bias of how we understand the world,” Navarrete reminds us. “If we really want to address the problems and questions that can help us improve the way that we understand the world, we have to include as many perspectives as possible.” Not to mention: “There are problems we need to solve here, on this land, right now,” Astolfi says. “And in my opinion, it’s so much more rewarding because you get to see the transformation with your own eyes.”

One of the most important things for scientists and researchers, and all of us, to do is consider our goals behind our actions, what’s motivating us. “Do we want to feel better about ourselves, or do we want to be collaborative and learn from other people?” Navarrete asks us to consider. “The way we approach collaboration with Indigenous and local communities is important; the outcome is going to be completely different depending on what our intentions are.” This may be uncomfortable sometimes, but we live in a world where we must be uncomfortable if we want to make things better, and that starts with cataloguing our privileges, biases, and research.

This is hard work. This can often be quite depressing, but I hope these scientists’ stories and efforts have given you the motivation to take action to make your research a bit more ethical, whether that be through integrating unique perspectives, collaborating with local communities, or giving back to the community that your work couldn’t exist without. Gomez left me with a valuable quote from Gregory Cajete, as we consider how certain Indigenous knowledge and ways of being and doing have been lost: “If the knowledge is so important, we’ll think of it again.” But we can only do that through collaboration and respect.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.