Book Review: The Equitably Resilient City

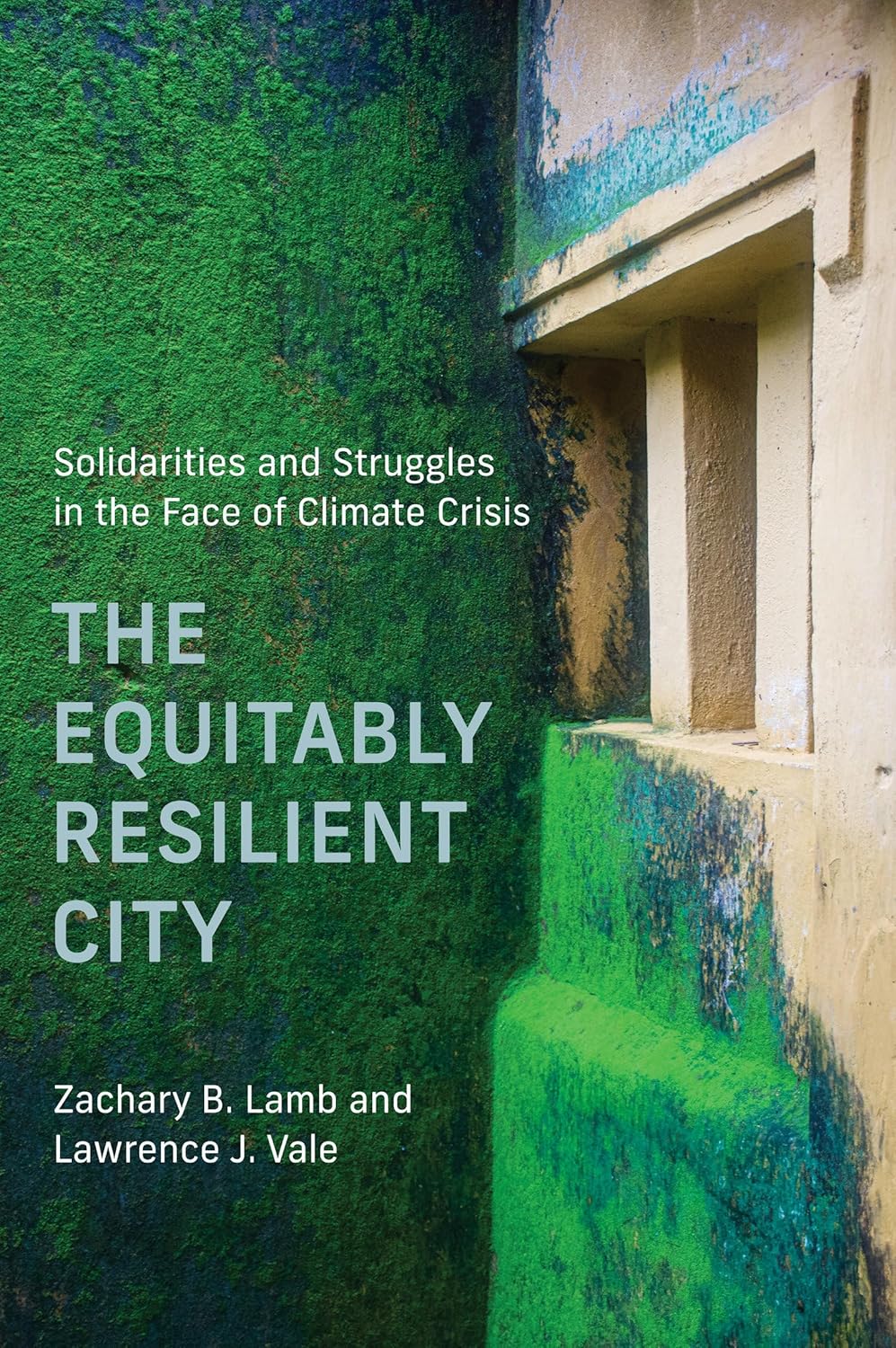

The world is, quite literally, both drowning and on fire. There is no sugar-coating the situation. As I spend my days doomscrolling and grieving over all that we have lost and will lose to the climate crisis, I also find myself deeply craving tangible solutions, so I picked up this book. The Equitably Resilient City covers twelve case studies of cities implementing urban development projects in response to climate crises and critically assesses whether the presented solutions are equitable. The authors are Dr. Zachary B. Lamb, an assistant professor of urban design at UC Berkeley’s Department of City & Regional Planning and Dr. Lawrence J. Vale, a professor of urban design & planning at MIT’s School of Architecture & Planning.

My motivations to read this book were not unlike the authors’ motivations for writing it. In an interview with Dr. Lamb, I learned that his architecture studies were interspersed with a wide range of experiences including a few years in environmental law and policy, a year as a carpenter learning about sustainable design and building, and work in “climate resilience consulting for affordable housing nonprofits and the [New Orleans] city government.” Through his career, he grew interested in “the politics of climate change adaptation in cities” and decided to pursue his doctoral degree with Dr. Vale, the book’s co-author. Dr. Lamb’s thesis focused on “New Orleans and Dhaka, two delta cities…quite vulnerable to sea level rise, coastal storms, and flooding” and investigated how these “cities make decisions about how they adapt, who benefits, and who’s harmed when those adaptation efforts are implemented.” These questions are central to both the book and to Dr. Lamb’s ongoing research.

The inequitable nature of climate impacts on marginalized communities is old news. As stated by the United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs, people of the global majority—namely low-income Black and brown communities and those who experience other dimensions of social inequity—are exposed to the most adverse impacts of climate change and are least able to recover. Yet, these groups contribute the least to global carbon emissions: The World Economic Form cites that the 74 lowest income countries collectively produce only 10 percent of emissions. The effects of climate injustice are undeniable in the United States, exemplified by Flint, Michigan’s long-running water quality issues, Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, and Elon Musk’s AI data centers in Memphis poisoning the air in historically Black communities. Closer to home in West Oakland, toxic waste, redlining practices, and other factors have driven the life expectancy in their predominantly Black population seven and a half years below the Alameda County average.

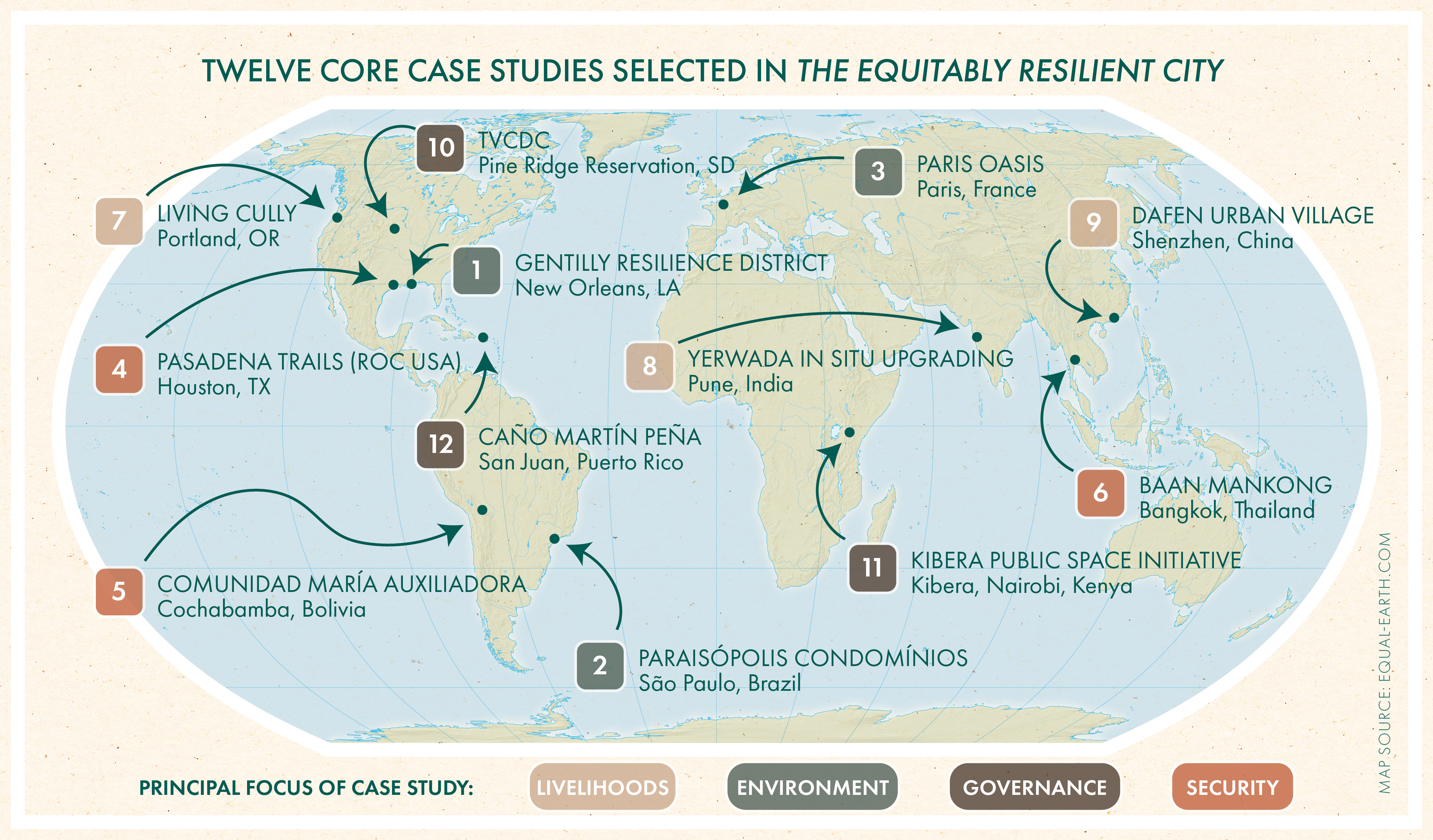

Clearly, interventions that center equitable sustainability are necessary, but how do you know if they work? The authors selected 12 cities spanning the globe that (1) have experienced some form of climate catastrophe and (2) have recently implemented built environmental interventions that (3) “seek to improve conditions for disadvantaged populations.” They assess these projects using four central dimensions or “LEGS”: Livelihoods—enhancing residents’ “ability to live affordably and decently,” Environment—both “reducing environmental vulnerability” and “supporting ecological vitality,” Governance—“[empowering] residents through self-governance,” and Security—protecting residents from displacement. These dimensions are examined across three scales: individual/household, project/community, and city/region; and each case study is assessed using literature reviews, interviews, and site visits.

Some of the most notable interventions to me were figurative structures rather than physical ones. Many projects centered participatory design and community feedback; included skill-building, educational, and leadership development programming; prioritized hiring local labor and using local resources; and reimagined property and land ownership through community land trusts and other ways of cooperatively owning and managing land. Case 10, set in Pine Ridge Reservation, the imposed homeland of the Oglala Lakota Nation, is a prime example that focuses on a community-led organization’s efforts to reimagine “housing, ecological and cultural regeneration, and infrastructure.”

Oglala activist Nick Tilsen founded the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation (TVCDC) in 2007 to draw upon Indigenous knowledge and “build an ecosystem of opportunity” for his community. The TVCDC’s activities include “sustainable housing, language revitalization, food sovereignty, workforce development, youth leadership, and social enterprise.” Their work is based on “regeneration [and] resilience” and “is as much about healing the human spirit as it is about green buildings,” says Tilsen. For instance, the TVCDC designed new affordable housing as circular structures with numbers honoring sacred rites and virtues from Lakota traditions. These clusters feature central communal spaces collectively designed and organized by residents. The TVCDC’s efforts are ongoing and they accept donations through their website (thundervalley.org). This case study and several others emphasize how tackling the climate crisis and remedying the impacts of settler colonialism and historical injustice are deeply interconnected endeavors.

Did The Equitably Resilient City satisfy my craving for actionable climate solutions, though? Yes and no.

Yes, in the sense that it was incredibly eye-opening to witness how people around the world have organized to protect and heal their communities from the impacts of both the climate crisis and societal injustice. The sustained struggle gives me hope that we can reimagine and rebuild both our physical and societal structures to better serve the planet and the people who live on it.

No, in the sense that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for climate justice and there will always be more work to do. Problems continually arise that require unique fixes that acknowledge the specific needs and historical experiences of affected communities. Many of the case studies come with various challenges and shortcomings, whether internal, external, or systemic. No solution is perfect, but the climate crisis is a multidimensional problem that calls for multidimensional solutions, solidarity, and a long-term fight. We cannot afford apathy, complacency, or surrender.

“All [the] dynamics that come up in the book are present in the Bay Area…whether we’re talking about the relationship between housing insecurity, eviction, displacement, gentrification, and climate change…We in the inner Bay benefit from a very mild climate and relative flood safety, but increasingly, people…are being displaced to places that often have longer commutes, more carbon intensive lifestyles, and more exposure to various forms of climate vulnerability,” says Dr. Lamb. One of the special things about UC Berkeley, however, is our culture of “commitment to being of service to our place, to our state, to our community, and to our region.” Beyond the many researchers on campus working to advance equitable climate action, some local and regional climate resilience efforts include the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, the Bay Conservation Development Commission’s efforts in sea level rise adaptation, grassroots organizing efforts led by the Black community, renewal of Indigenous land stewardship and fire practices, dam removals, and food justice movements. As Dr. Lamb says, it’s a critical time to be “investing in local movement building [and] building connections between local movements that are trying to do this work.” As much as there is to grieve, there is also plenty worth saving and the work is always better done in community.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.