Step aside, plastic

A new type of sustainable packaging

Instead of putting plastics in the ocean, this Bay Area team uses the ocean to replace plastics. Conventional thin film plastics, derived from fossil fuels, devastate ecosystems and generate nearly half of global plastic waste. Yet industries like food and fashion depend on thin films for cheap, lightweight packaging. To break this dependence, San Leandro startup Sway is creating compostable, seaweed-based plastics, with support from UC Berkeley’s very own graduate Armina Mayya (BS ’24, MS ’25) and UC Berkeley Professor Robert Ritchie.

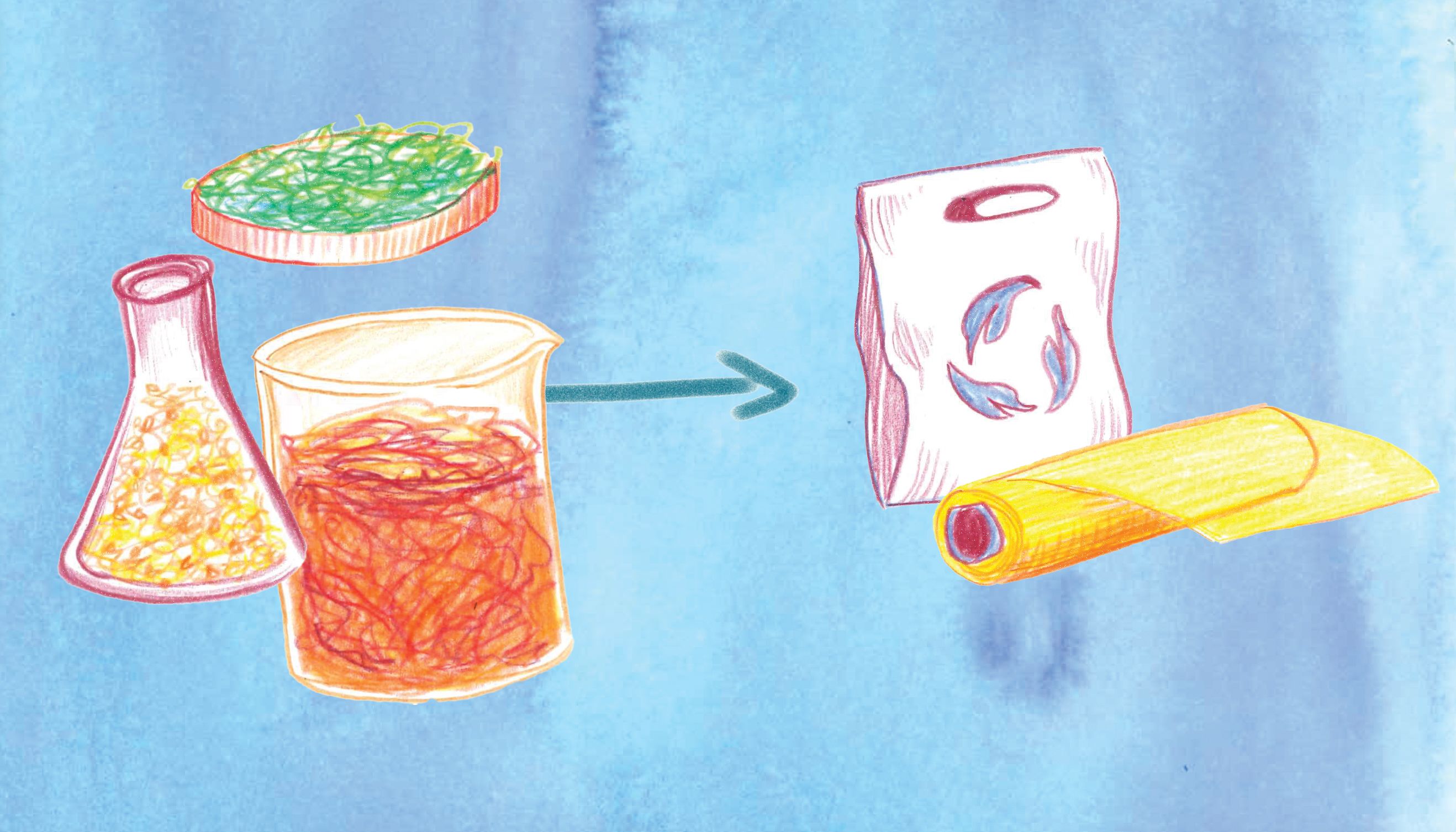

Sway’s packaging mimics the feel of plastics while including regeneratively cultivated seaweed. This marine crop thrives on sunlight and seawater, with little need for freshwater, fertilizer, or human intervention. Mayya explains, “Seaweed is suspended in water using seeding ropes, and it grows vertically downwards along the rope in a dense forest that can restore lost ecosystems.” Once harvested, the seaweed is dried into powders and processed in the same facilities as standard plastic bags but without toxic chemicals or hazardous conditions. After use, the packaging can even break down in under 90 days in an industrial composter, a rate similar to orange peels.

Mayya and Sway apply science and engineering to ensure that seaweed can drop into the same manufacturing processes as standard plastics. If raw seaweed were simply dried and used, the seaweed would burn upon heating instead of melting and flowing through equipment. Sway solves this in two ways: (1) through an aqueous product line they call Firstwave™, and (2) through a product line they call Thermoplastic Seaweed™. In the case of Firstwave, Sway introduces plant-based additives that enable seaweed to gel in water and create thin films. In this way, Firstwave films avoid the high temperature processing necessary for conventional plastics. With this first-generation material, Sway produces both translucent product windows, like those used on pasta boxes, and pouches, like those used for online-ordered clothes.

Sway’s Thermoplastic Seaweed line is being developed to work within globally scaled manufacturing systems that operate at extreme heat. This process begins by turning a mixture of plant-based additives and seaweed extract into a meltable resin, compressed into uniform pellets. The pellets can be combined with an array of compostable polymers to create a myriad of end products. For Sway’s Thermoplastic Seaweed film, the pellet blend is melted and blown into thin film, forming a 50-foot bubble tower of molten material. As the walls rise, they cool and solidify until rollers flatten and tune the film thickness. For mass production, this bubble process runs year-round.

To an outsider, this bubble seems like a Rube Goldberg machine: an incredibly complex process to accomplish a common goal. Yet, the bubble process (otherwise known as blown film) enables bags to be made thinner without sacrificing strength. Because the film is stretched in multiple directions during processing, blown film has much higher puncture and tear resistance than films made by single-direction casting. This toughness means lighter, stronger bags that use less material than the first-generation films.

The bubble process depends on a range of proprietary additives. Though used in small amounts, these ingredients determine how the seaweed flows, prevent it from sticking to equipment, and tune composting lifetimes. Mayya notes that while similar additives have been tested with other plant-based packaging, their interactions with seaweed are still poorly understood.

To refine the material, Mayya and other engineers at Sway rigorously test thermal properties of the pellets, which dictate the final durability of the bags. They measure heat absorbed and released by the pellets as they ramp temperature up and down, checking for the melting temperature and the temperature range where the polymers gel and solidify into ordered structures. From there, they tune the cooling rate to achieve a ratio of ordered polymer chains and disordered polymer chains. The more ordered the chains, the stiffer the bag when pulled. Since these microscopic patterns are invisible to the naked eye, chemistry expertise is essential for this characterization.

Mayya and Sway love that their lab work is guided by ethics and ecological partnership. When asked about her field of study, Mayya smiles, “I always wanted to improve sustainability. I am excited to be part of the compostable packaging movement.” Seaweed can be a great snack, a coastal treasure, and a heart-warming packaging material. Though, Mayya adds, “While I feel like a chef in the lab, I do not recommend eating the packaging.” The packaging is designed to be tasty for soil microbes, not humans.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.