The Redwood Center gets its twentieth ring

An interdisciplinary approach to studying the brain

What would it mean to understand the brain? One view is that to understand, we must know the exact electrochemical pathways involved when an organism performs a task. Alternatively, perhaps being able to predict neural responses to stimuli, such as sounds or odors, is sufficient. Or, more abstractly, understanding could come from explaining seemingly complicated observations with simple principles. Even amongst neuroscientists, there is no clear consensus. Regardless of the exact definition, most would agree that the vast space of open questions requires various strategies to answer: collecting and analyzing neural data, developing theories of neural circuits (how neurons connect to perform a function), and building systems inspired by the brain, as starting points. This interplay between data, theory, and engineering is central to neuroscience and drives the research at UC Berkeley’s Redwood Center for Theoretical Neuroscience (RCTN).

Known colloquially as the “Redwood Center,” or “Redwood,” RCTN aims to develop mathematical frameworks and computational models of the neural mechanisms underlying sensory perception, motor function, learning, and cognition. The research at Redwood is interdisciplinary, and its members come from a variety of departments including neuroscience, vision science, physics, mathematics, engineering, and computer science. Recently, Redwood celebrated its 20th anniversary at UC Berkeley on July 1, 2025, commemorating the day with a symposium attended by current and former members.

In his opening remarks, RCTN Director Bruno Olshausen, professor of neuroscience and vision science at UC Berkeley, emphasized the mission of the center: to approach the brain as a complex computational system governed by mathematical and physical principles. He highlighted areas of active research within the center—including the physics of computation, mathematics of representation, and mesoscopic-level (beyond single-neuron) modeling—pointing out the ways in which each contributes unique and complementary insights into how the brain works. These insights, Olshausen says, can help neuroscience build a clearer understanding of the brain “all the way down to the cellular level and molecular mechanisms, and how [neural circuits] function together as a system.” From there, Olshausen presented the day’s schedule: three moderated panels, mini talks, and member spotlights. Each panel represented one of Redwood’s core pillars, foundational themes that unify the center’s interdisciplinary research:

Neuroscience: the study of neural systems, including sensory perception, learning and memory, and cognition

Theory: principles grounded in mathematics and physics to describe neural activity

Machine intelligence: combining neuroscience and theory to build systems that can sense, reason, and/or interact with the world

The goal was to foster discussion between panelists and audience members on each of these topics. Mini talks and member spotlights also provided a more personal lens into the Redwood community, allowing current students and alumni to reflect on their time at RCTN and showcase their current work.

Olshausen later reminisced that there was “a huge turnout from people all over the country, all over the world, from the past 20 years, and it was remarkable to see.” The sessions aimed to take advantage of this turnout, highlighting Redwood culture over the years and how the center has influenced alumni’s professional careers. Opening remarks transitioned into a brief history of the Redwood Center and how it came to be at UC Berkeley, which set the stage for the day’s events.

A brief history of the Redwood Center

Redwood first started out as the Redwood Neuroscience Institute (RNI) located in Menlo Park, California. It was founded in 2002 by Jeff Hawkins, a former UC Berkeley biophysics graduate student and founder of Palm, Inc. (known for the PalmPilot). As a private non-profit research group made up of research scientists and postdoctoral fellows, RNI’s mission was to develop theoretical frameworks for how the cerebral cortex—a part of the brain that plays an important role in perception, attention, memory, and more—processes sensorimotor signals. The atmosphere and scientific freedom was special, recalls Fritz Sommer, now an adjunct professor in neuroscience at RCTN. “We could think and discuss around the clock. Invited speakers would start their talk at 2 p.m., and we would break at 7 p.m.” In July 2005, RNI was gifted to UC Berkeley and became RCTN, with several RNI members also making the transition to UC Berkeley. Today, the Redwood Center has grown to six principal investigators and dozens of students and postdoctoral fellows.

As the history tour concluded, attendees geared up for the anniversary symposium’s two morning panels: neuroscience and theory, two pillars that have defined RCTN’s mission for the last 20 years.

Neuroscience and theory: from neural activity to abstract principles and back

Discussions during the morning panels revolved around two questions: what is the job of theoretical neuroscience, and what can it provide for neuroscience at large? The general consensus was that while neuroscience focuses on studying the mechanisms underlying perception, learning, behavior, and cognition via computational modeling or data analysis, theory takes a step back to ask what principles might explain such phenomena. One definition, then, of theoretical neuroscience is (1) identifying the problems that the brain is trying to solve and (2) developing theories (at the neuron, circuit, or brain region level) of how such problems are solved by real biological processes.

A main theme in the neuroscience panel was the necessity of developing better analyses to understand the abundance of large-scale and complex neural data collected within the last few decades. This is where theory comes in. As Sommer explains: “The job of a theorist is to make the world simpler again.”

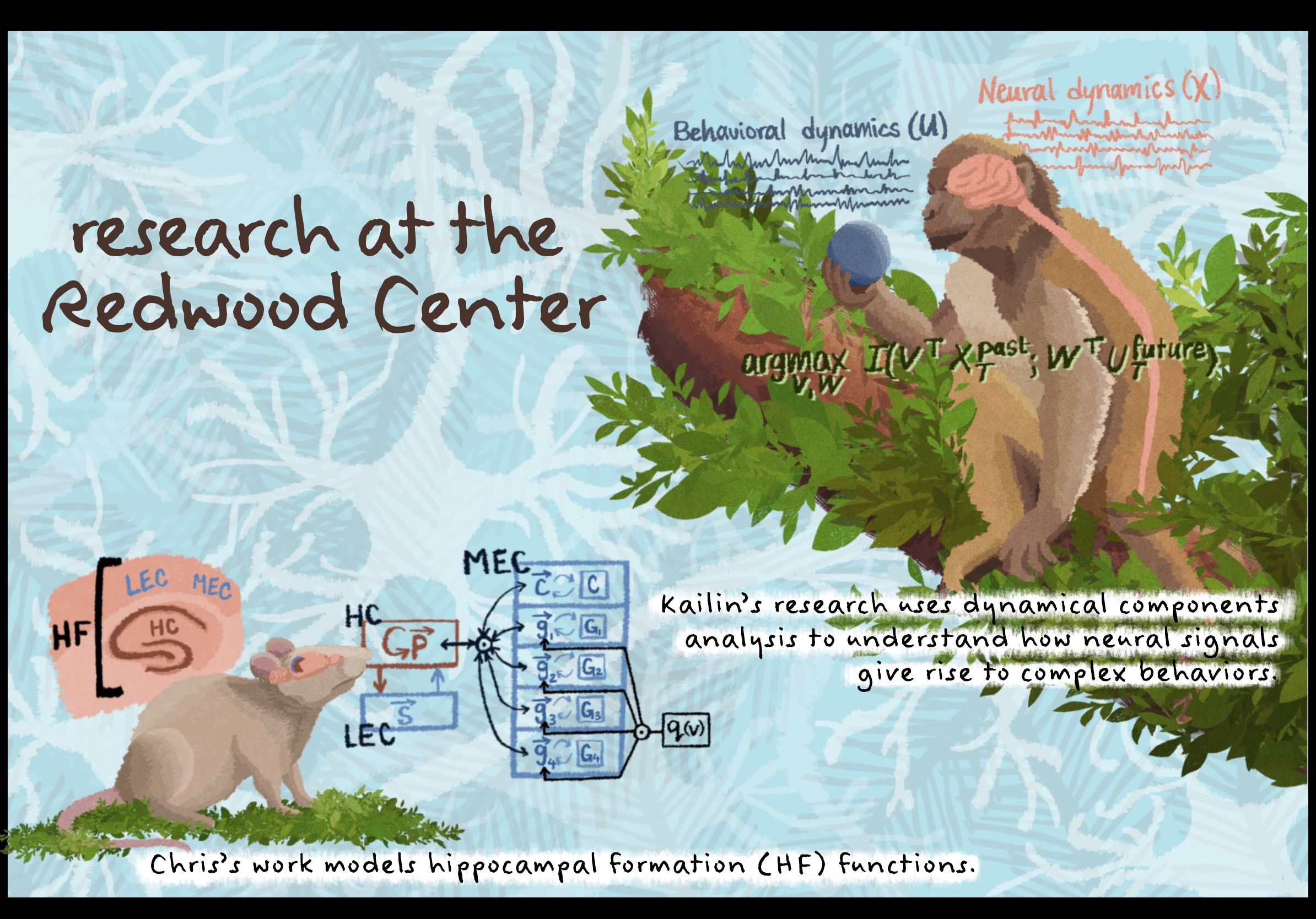

Analyzing large datasets requires building new data-driven methods, which theoretical neuroscience can do using principles from mathematics. Kailin Zhuang, a graduate student in Kristofer Bouchard’s lab, explores how natural behaviors like human speech are produced by the brain. “Natural behaviors can be highly complex. [They are] high-dimensional, composed of many features, and extracting the relevant features can be difficult,” she explains. To make sense of such data, scientists use dimensionality reduction techniques, the most widely used being principal component analysis (PCA). Such methods lower the number of variables while retaining important statistical structure, distilling the data into its key components. But not all dimensionality reduction techniques are created equal; some simply aren’t well suited to certain types of data. Zhuang notes, “In time series [data] where both noise and dynamics contribute to the overall variance, PCA is prone to extracting [features] from noise rather than [neural activity].” For her data, Zhuang uses dynamical components analysis (DCA), a method developed by the Bouchard lab. DCA draws from information theory, a branch of mathematics that studies how information in signals is processed and transmitted, and finds features that maximize the mutual information between past and future data points.

This is termed “predictive information.” She explains, “[Predictive information] describes how much we are learning about the future based on what we have observed in the past.” While PCA focuses on variance, DCA takes into account the temporal aspect and extracts dimensions that maximize predictive information, making it a stronger tool for uncovering dynamic patterns in complex neural and behavioral data. As the number and size of datasets grow, so will the need for better analytic methods. Zhuang’s work demonstrates how blending computational neuroscience with mathematical theory can drive the development of these techniques and help deepen neuroscientist’s understanding of complex natural behavior. The kind of work described above studies what features (or mechanisms) underlie neural activity associated with a behavior. Why these phenomena occur, or what principles govern them, is a different question. “[To] think about what the system is trying to do, we go to theory,” Olshausen says. Instead of digging through data, a theory-first approach hypothesizes how, given known physical and mathematical properties of the world, a neural system organizes to perform a specific function.

An example of this is the work of Chris Kymn, a postdoctoral fellow and former graduate student in the Olshausen lab. He studies the governing principles of the hippocampal formation (HF), which consists of the hippocampus and parts of the neighboring entorhinal cortex. These structures both play key roles in memory and navigation. In the 1970s, scientists identified a type of neuron in the hippocampus, which they termed a “place cell,” that fires when an animal is in a specific spatial location. Decades later, “grid cells,” which encode position using a grid-like coordinate structure, were discovered in the entorhinal cortex. Although scientists now have more clues about how the brain represents location, it is still unclear why the brain would encode space in this way. “Neuroscience has amassed an amazing amount of experimental observations, but we often don’t understand how the design or structure of neural circuits implement core functions,” Kymn points out.

More recently, studies have suggested that the HF represents information using compositional structure, which allows combining familiar factors to make sense of novel experiences in an efficient way. This ability is necessary for organisms navigating in the world. For example, say you’ve walked into a new building on campus. You can identify and navigate to landmarks, such as bathrooms and stairways, without having previously explored the building. Presumably, this is because you have learned general features of building layout through past experiences. This is the power of compositionality: it provides the benefit of expressing complex and novel situations while using a relatively small amount of resources. Generalizing to novel settings is a computationally difficult problem, yet the brain seems built to handle this.

In an effort to understand the implementation of HF function, Kymn and collaborators recently developed a normative model that proposes mechanisms for compositional structure. Normative modeling puts forth fundamental principles that, if satisfied, allow a system to achieve desired functions or properties. In this case, the desired property of the HF is a representation that can be used to navigate physical or abstract space (e.g. of concepts). The primary principle imposed in this model, motivated by experimental evidence, is a spatial representation that is compositional and resource efficient. Kymn’s work provides a theory that explains phenomena observed in the HF, such as grid and place cells; it proposes why these cells are organized this way. It also offers testable hypotheses—for example, about specific biophysical interactions between neurons and connections between grid and place cells—for experimentalists. A theory-first approach, built upon existing neurobiological evidence, thus serves as a powerful framework for generating targeted experiments and deepening our understanding of HF and spatial representations in the brain.

(Toward) building intelligent machines

Though not explicitly about the brain, machine intelligence can be thought of as an application of neuroscience and theory to engineering. In the third panel, former RCTN fellow Dr. Dileep George likened the current path of artificial intelligence (AI) to a period in the history of airplanes. For decades, buoyancy-based airships, like hot-air balloons and zeppelins, were thought to be the most robust form of air transportation. Although making them larger allowed for more cargo capacity and longer flight durations, airplanes eventually dominated as the primary means of flying. Just as with airships at the time, George pointed out, current AI is more impressive than ever before. Yet, there are shortcomings that suggest simply scaling up the models is not feasible. Indeed, recent reports have indicated that AI progress, driven primarily by larger models trained on more data, is slowing. Furthermore, even for current models, there is a glaring issue: the scale of energy consumption needed to power AI.

A 2025 report from the International Energy Agency estimates the power required to query an AI model to generate text as about two watt-hours (Wh), and around 25 times that for short video generation. As a reference point, a smartphone requires roughly 20 Wh for a full charge. So much energy is required to serve these models that Amazon and Google have recently invested in nuclear power to meet energy demands for their AI services. In contrast, biological systems have evolved to be highly energy-efficient. A jumping spider, which has a complex visual system and can stalk prey like a cat, is powered by roughly one fly per day. “There’s a stark difference between the data centers powering AI and these small brains,” Olshausen says. One approach might be for engineers to turn to neuroscience for inspiration.

Connor Bybee, a former postdoctoral fellow and graduate student at RCTN, aims to understand principles of biological computation in cells and brains and how they can be applied to designing more efficient machine learning algorithms and computer hardware. Traditionally, the standard model of a neuron adds input signals together to produce an output. However, there is substantial evidence that dendrites, the parts of neurons that receive inputs from other cells, can perform multiplication. In a simple second-order multiplicative model, a neuron could receive inputs (numerical values) from two other neurons and output the product. A slightly more complex model, motivated by evidence that dendrites implement higher-order interactions, might have neurons that receive inputs from three, four, or more neurons. Although higher-order interactions can capture statistical information that second-order networks cannot, they have received little attention due to claims that they require more resources.

In recent work, Bybee and colleagues developed neural network algorithms that use higher-order interactions in a physics-inspired framework. They showed that compared to second-order networks, these provide faster and more accurate solutions to a class of hard computational problems. A key result in Bybee’s approach is that it can solve these problems more efficiently, with fewer variables and connections, than second-order approaches. This means “fewer circuit elements, fewer transistors, less required memory, and fewer wires,” says Bybee. “These principles could be used to eventually design novel computer hardware.” Indeed, there is active research in building computer hardware suited for efficient higher-order processing. These algorithms could also provide clues for how biological brains compute at such low power compared to artificial systems and could plausibly be implemented in the brain.

Despite this promising direction, Olshausen cautions against blindly adopting biological principles in machines. “There’s a different set of problems and challenges to solve. Certainly, there are things we can learn, but you need to acknowledge the differences up front.” For better machine intelligence, it may be even more important to understand the nuances of biological intelligence: not just how systems work, but also—connecting back to theory—why they work the way they do.

Redwoodians: life outside the research

Beyond discussions of science, the anniversary event was a celebration of the researchers that make up the Redwood Center. The spotlight sessions gave attendees a chance to show how their time at Redwood shaped their lives, with many of these personal stories emphasizing how the unique and collaborative nature fostered both professional and personal growth. One of the spotlights highlighted Adrianne Zhong, a recent doctoral graduate from Mike DeWeese’s lab who said, “There’s no academic environment I’ve been in that’s been more inviting and welcoming than the Redwood Center.” This sentiment was echoed by others who described how pivotal the environment of RCTN was to their development as scientists. Some have stayed in academia, while most go to industry with roles ranging from research scientists at AI companies to biotechnology startup founders. One of the most popular anecdotes brought up by current members and alumni alike were the hour-long Redwood seminars. These meetings provide opportunities for attendees (not always RCTN members) to trade ideas, ask questions, and find new collaborations. A variety of disciplines are represented at Redwood seminars, but the common ground is the drive to understand principles of computation in brains and machines. The diversity of perspectives contributes to the explorative culture that defines the Redwood Center. One alumnus recounted a seminar where the presenter had only reached slide three of 25 in an hour that had been taken up with investigative questions and tangents. Freedom of exploration, Sommer explains, is crucial in a research environment; it is often as important as the scientific training. There are ample opportunities for people to socialize in Redwood; in addition to spontaneous discussions at the whiteboards, lunches and weekly tea times lead to conversations between students, postdocs, and professors across labs, and with researchers from outside the center. Regardless of their paths, many member spotlight sessions described RCTN’s emphasis on curiosity-driven inquiry. As Sommer elaborated, “[We] often think about this intrinsic motivation… once [this passion] latches onto a specific question, it’s the driver of why people figure out stuff, and I think that it’s very important to realize that you cannot force this.” By valuing this process of exploration, discovery, and openness as much as the outcome itself, RCTN fosters a unique environment where researchers are free to find their own paths.

Looking forward: the future of Redwood

During the neuroscience panel, a student asked, “If we were to look back from the future, is what we’re looking for [i.e., how organisms can navigate easily in new environments, or how the brain computes with relatively low power] contained in the data we have now?” While evocative (and likely true), it only considers part of the picture. Take, for example, a dataset from 20 years ago. Applying modern analytic techniques, such as those used by Zhuang, may uncover new insights. But necessity is the mother of innovation. With smaller datasets, such methods may not have been developed in the first place. It is not just about the complexity of the data either; new hypotheses, such as those proposed by Kymn’s work, and well-designed experiments have increased the richness and quality. Furthermore, the tools needed to collect and analyze this data would not have advanced without innovations, similar in flavor to Bybee’s research, in engineering and computation. While it is true that we do not analyze data the same way as we did 20 years ago, it is experiments, theory, and engineering advancing together that have led to the field’s growth.

So, what if we were to look back at ourselves now from the future? Given our data, would we be able to answer our questions? At the symposium, panelists agreed that both theories and available experimental observations are far from complete. RCTN, a center that combines basic, exploratory research in neuroscience, theory, and machine intelligence, occupies a unique area of research equipped to help address these questions. Now, in a period where modern-day AI dominates discourse on intelligence and computation, yet appears to be hitting a ceiling, the type of research at RCTN is more necessary than ever. Just as importantly, at the heart of Redwood is an environment where freedom and diversity of research are encouraged, as well as a deep respect for the complexity of the brain. “It’s a monumentally difficult problem,” says Olshausen. “To quote my colleague Jerry Feldman, ‘You have to have a sense of humility to study biology.’ These problems will be with us for quite some time.” Despite this, Olshausen is optimistic: “The future is bright.” At the next Redwood symposium in 10 or 20 years, attendees will be discussing new brain imaging techniques with new datasets, new theories and analysis tools, and progress in AI and robotics. Perhaps at that point, neuroscientists will even have started to agree on what it means to understand the brain.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.