Ancient history, modern evidence

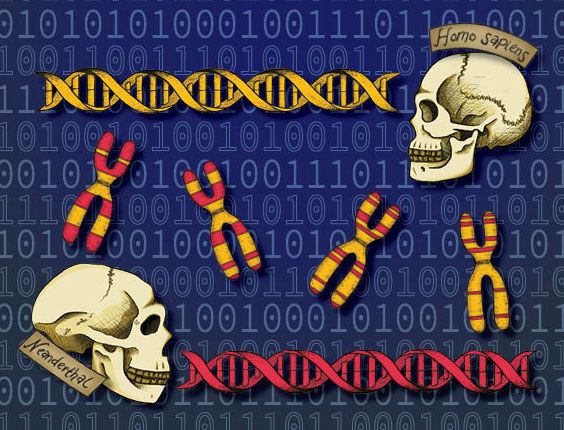

In the last two centuries, the paleontological study of ancient fossils combined with the power of modern genetics has revealed unknown aspects of human history. One of the most intriguing findings is the presence of Neanderthal genomic sequences in the genomes of modern humans, a result of interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis about 50 thousand years ago. Dr. Priya Moorjani’s lab in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at UC Berkeley uses computational tools to probe ancient genetic data for signatures of this interbreeding and the resultant effects on modern human populations.

To dissect the evolution of Neanderthal gene segments in humans, Moorjani’s lab used hidden Markov models to analyze genomic data from 59 ancestral hominins and 275 present-day humans using high quality Neanderthal genomes and Sub-Saharan genomes with minimal Neanderthal ancestry as references. They found that gene flow between the two species occurred over a period of about seven thousand years when the different species continuously interacted. After this initial gene flow, secondary genetic events contributed to the pattern of Neanderthal gene segments present in modern humans. They identified several gene loci that underwent positive selection in ancient populations following inital interbreeding, containing genes such as BNC2, involved in skin pigmentation, and TANC1, involved in neuronal signaling. Whether these gene variants are practically beneficial to the modern human will be the subject of future studies.

Archaic genetic events triggered by the interbreeding of different hominin species are a source of genotypic diversity in modern human populations. Moorjani’s lab highlights important connections between archaic human history and modern-day genetics, an endeavor valuable for understanding human diversity and disparate health outcomes.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.