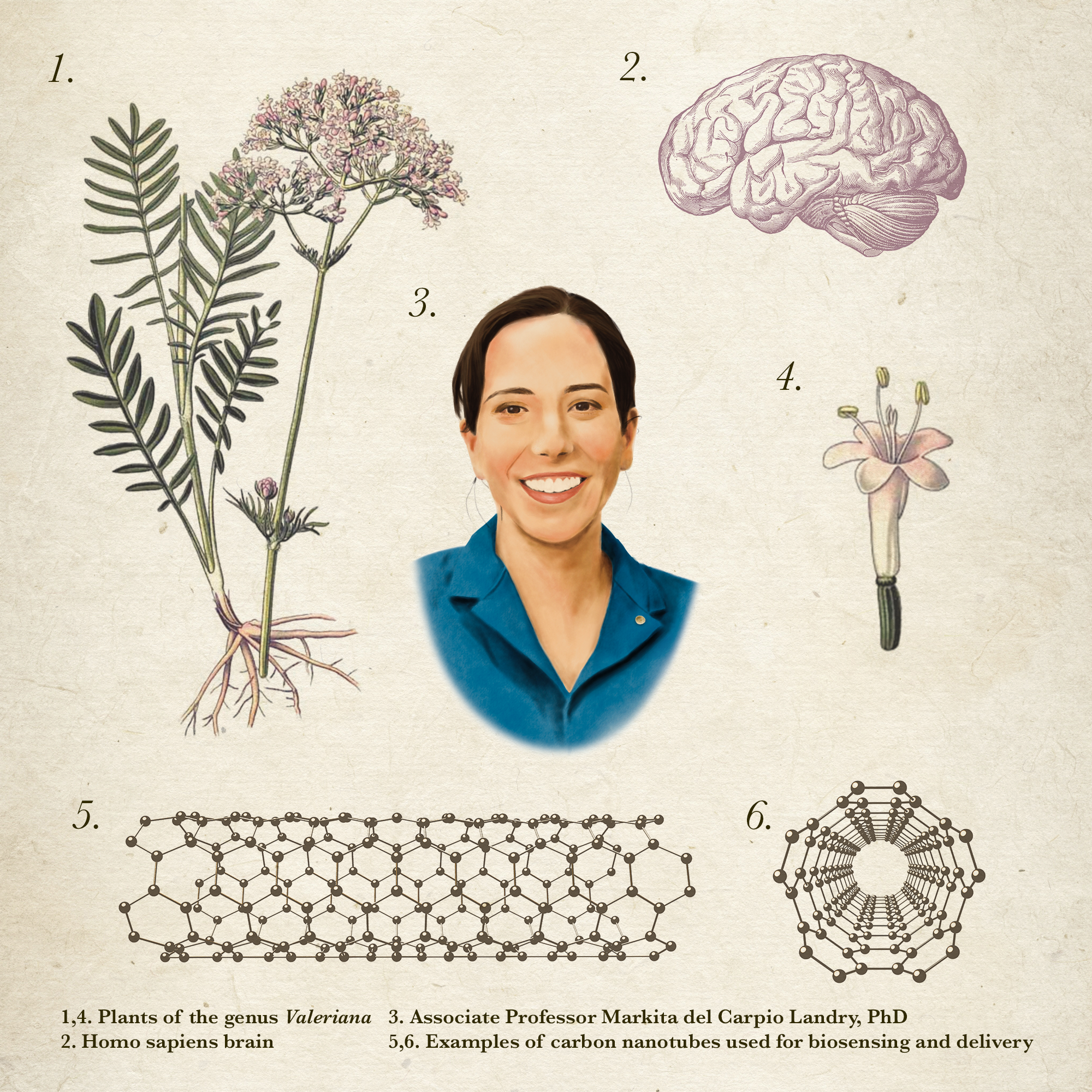

“I never thought as a single molecule physicist that I’d be doing any field work.” Although she laughs, Dr. Markita del Carpio Landry’s comment raises an interesting point—how many chemical physicists travel to Bolivia to investigate plant extracts for treating neurodegenerative diseases? But on further inspection, it seems she makes her career out of navigating new and diverse intellectual terrain.

Her remarkable scientific trajectory traces back to high school. Her family immigrated to America from Quebec, and she found herself learning in an English-speaking classroom for the first time. She gravitated toward math and science because “those made more sense outside of the linguistic barrier.” After discovering a passion for research in college, Dr. Landry pursued her PhD in chemical physics at the University of Illinois, followed by a postdoctoral appointment at MIT, where she studied phenomena ranging from the molecular to the nanoscale, taking on new levels of complexity as she progressed through her scientific training.

Although she has always expanded into new topics by following her curiosity, as a professor at UC Berkeley, Dr. Landry finds that her work is often shaped by her students as well. She notes, “You can run a lab by setting research directions … but you miss out on the best part of [UC] Berkeley, the intellectual capital that [the students] bring to a research project.” Her first students were eager to tackle a project outside of her comfort zone: genetic engineering in plants. Gene editing is used in agriculture, but there are major obstacles preventing efficient gene delivery due to plant cellular defenses. By leveraging her experience and cultivating her students’ curiosities, her lab developed new methods that enable gene insertion with nanomaterials. “Those tools … became a valuable way to merge our experience [in nanotechnology] with unknowns in biology.”

Now, Dr. Landry is taking the next leap in her research: exploring the vast world of Bolivian ethnobotany and pharmacology. She first encountered traditional plant-based medicines through her Bolivian mother. “My family and other community members have been reliant on plants for treating everything from headaches to even psychiatric disorders for centuries.” Supported by a Guggenheim fellowship, she aims to explore the medicinal components and molecular mechanisms of these medicines. She believes that testing plant extracts on laboratory mouse models of neural disease will help provide insights into their beneficial effects.

Dr. Landry admits that there are many intricacies in embarking on a scientific study in this field, including that “communities [in Bolivia] are rightfully protective of the knowledge they’ve built, especially in the face of pressures on traditional medicines and political influences both inside and outside the country.” Therefore, a central commitment of her work is “accessing [indigenous plants] in ways that are ethical and respect the amount of knowledge that has been built over centuries in these communities.”

Indeed, this cultural knowledge is immensely important for the success of the project. Instead of blindly screening plants for unique biomolecules, Dr. Landry and her team painstakingly combed through records and oral accounts of traditional applications for thousands of plants. There were three plants consistently mentioned for treating central nervous system disorders. She notes, “When multiple independent sources are telling you the same thing…it’s a good reason to focus on those candidates.”

Looking to the far future, it may be possible to use the tools she has helped develop to upregulate genes associated with biomolecules of medicinal value. However, Dr. Landry realizes the difficulties ahead. “This is a very out-there project for us, and that’s coming from a lab that does plants and neuroscience somehow simultaneously.” Luckily, if there’s anything Dr. Landry has demonstrated over the years, it’s that she can rise to meet these challenges.

This article is part of the Fall 2025 issue.