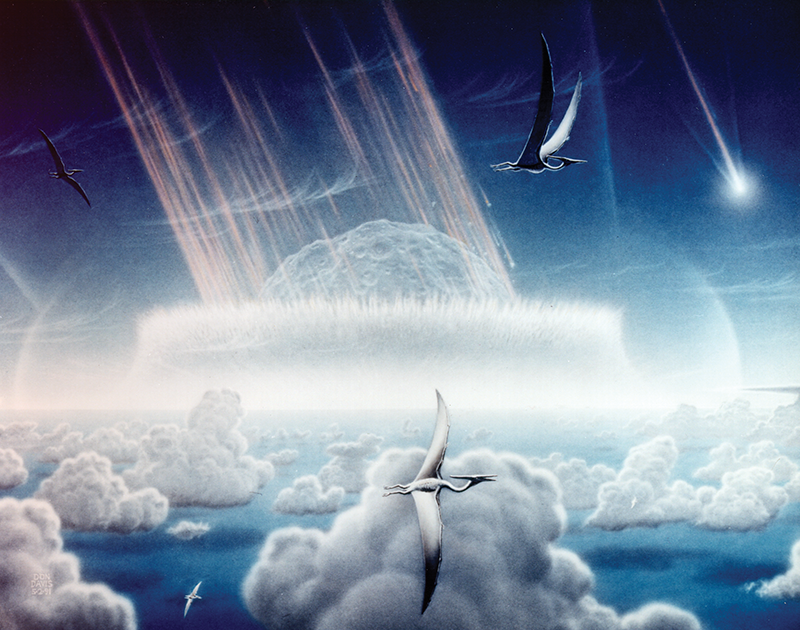

Ask almost anyone about the fate of the dinosaurs and they’ll tell you they went extinct millions of years ago. But T. rex and Triceratops weren’t the only species that were wiped out. During the mass extinction that occurred at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary 66 million years ago, an estimated three-quarters of the animals, plants, and microbes living on Earth also disappeared from the fossil record. Recently, a group from the Berkeley Geochronology Center and the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at UC Berkeley, led by Professor Paul Renne, brought us one step closer to understanding what kind of catastrophe brought about such widespread devastation.

Credit: NASA

Credit: NASA

The cause of this mass extinction “has been one of the biggest questions in earth and planetary science for years, and has an incredibly strong focus on the Berkeley campus,” Renne says. Two major hypotheses have been proposed to explain the cause of the K-Pg mass extinction. Many paleontologists have long favored a model in which relatively gradual climatic changes brought about by widespread volcanic activity stressed ecosystems, making it increasingly difficult for them to support a large number of species. In 1980, however, scientists from UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory proposed that an immense asteroid collided with Earth around the time of the K-Pg transition. Such an impact could have drastically and rapidly changed the planet’s climate, bringing about a mass extinction. This hypothesis was supported several years later by the discovery of a large impact crater, called the Chicxulub crater, near the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico.

Debate over these two models is still ongoing. According to Renne, “there’s always been a really healthy controversy around this subject. I wouldn’t say that we’re any closer to having a unanimous opinion now than 30 years ago.” Therefore, his research group set out to determine whether the mass extinction occurred at the same time as the Chicxulub asteroid impact. Along with researchers from the Netherlands, they determined more precisely than ever the age of rocks from the K-Pg boundary and found that the timing of the mass extinction almost perfectly coincides with the age of the Chicxulub impact structure.

Determining the precise age of a rock involves a number of steps: collecting the rock in the field, separating out the individual mineral grains within each rock, and analyzing the elemental composition of each grain. Renne’s group was able to make more exact estimates of the ages of their rock samples than previous studies because they spent significantly more time analyzing data from what are called the “standard” samples, markers of known age to which samples of unknown age are compared. While previous studies had dated K-Pg rocks to an uncertainty of around 120,000 years, Renne’s group dated the rocks to an age of 66 million ± 32,000 years. To put this number into perspective, this corresponds to an uncertainty of only ± 6 days in the age of a 50-year-old person.

The fact that the timing of the K-Pg mass extinction coincides perfectly with the time of the Chicxulub impact provides strong support for the impact hypothesis. However, the asteroid may not be the only cause. More gradual changes in Earth’s climate due to prior volcanic activity could have stressed ecosystems, which may have been unable to cope with the dramatic effects of the asteroid impact. Renne and his students hope to gain a better understanding of the Earth’s environments 66 million years ago, as well as the changes they underwent, by studying rocks from the K-Pg boundary. Bill Mitchell, a graduate student involved in the work, hopes to determine what the mass extinction “looked like while it was happening.” Not only does studying this particular time in geologic history provide “our best chance to see with high resolution how fast things died out,” Mitchell says, it could also inform current assessments of ecosystem health. If we knew more about the changes that occur during a mass extinction, we might be able to use this information to look out for warning signs in the future, especially as climate change alters environments around the world in unpredictable ways. Through the work of Renne’s group and others, we may learn not only about the downfall of the dinosaurs, but also what to look out for in a planet undergoing change.

This article is part of the Fall 2013 issue.