Society’s needs and desires change constantly. New demands eventually result in novel technologies and scientific advancements that cater to the general consumer. During the transition from lab bench to marketplace, the implementation of such new technologies doesn’t always consider the cultural needs of specific users. In the case of American Indians, these considerations may include how to design energy-efficient homes while still maintaining native architecture, or how to install wind farms on sacred lands. UC Berkeley professors and students are taking strides to aid local native communities by helping to assimilate new technologies into their long-standing and vibrant cultures.

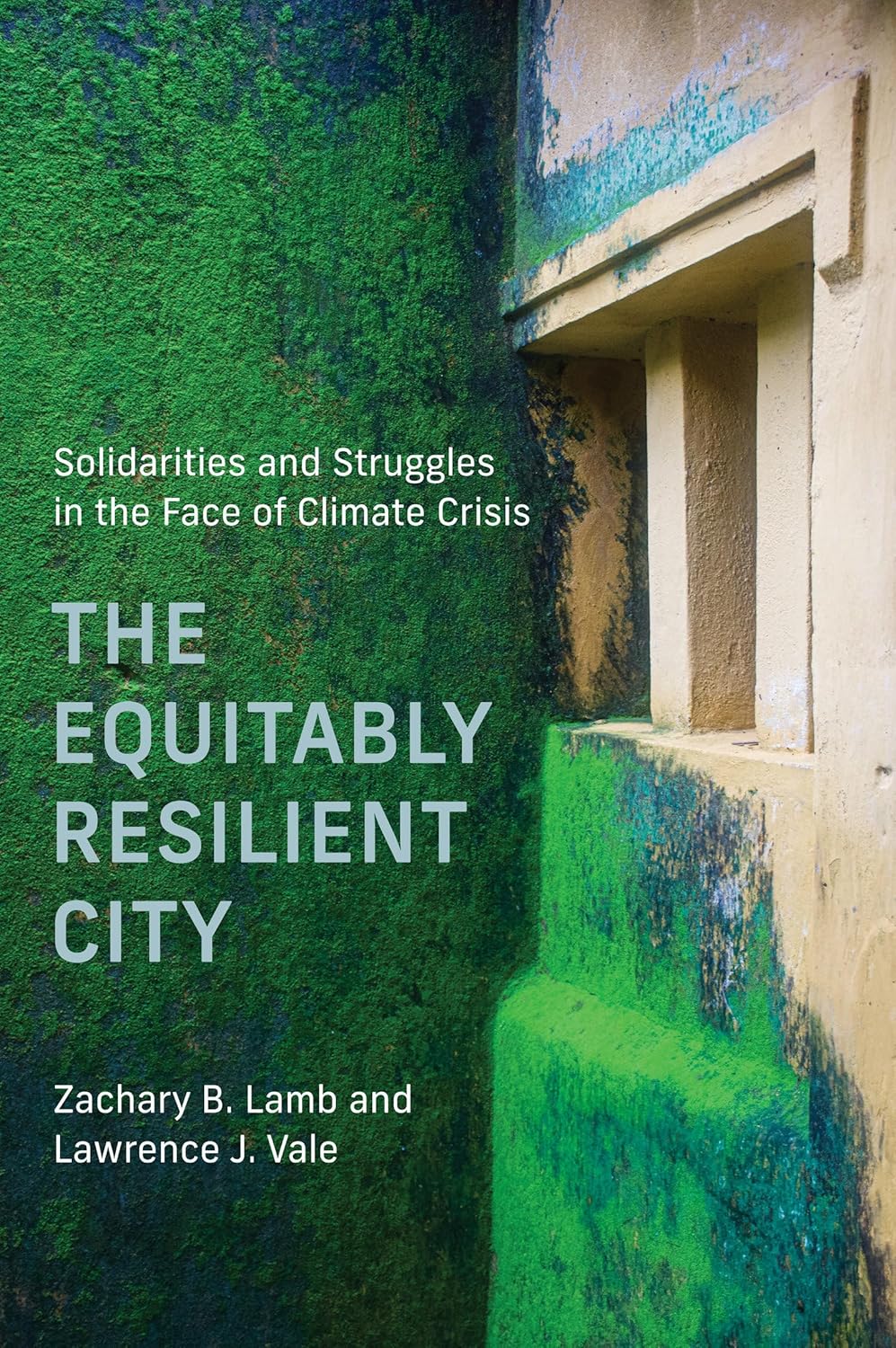

One successful collaboration between students and the local community joined mechanical engineering Professor Alice Agogino with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation, an indigenous tribe of northern California. This local native community initially came to the Cal chapter of AISES (American Indians in Science and Engineering Society) to describe their situation and ask for help from Native American Cal students. The Pomo people had been living in disheveled, formaldehyde-ridden trailers and much of their money was spent on burning propane for energy. Fortunately, members of AISES were able to direct the needs of the Pomo people to an expert in leading successful culturally sensitive design projects. Agogino accepted the challenge to design modern, environmentally friendly housing that would meet the specific needs of the Pomo Nation. But long before any blueprints were laid out, trust needed to form between the two parties.

Academia tends to work within specific deadlines, but building trust and a sustainable relationship with a local community can take an unpredictable amount of time. Initially, a member of the Agogino research group, PhD student Ryan Shelby, acted as the sole liaison. Coming from an underrepresented community in Alabama, Shelby entered the project with a personal perspective and sympathy for the Pomo people. His unique background and personable demeanor naturally placed him at the cornerstone of this long-term partnership. Once mutual understanding developed, the Berkeley group set out to address the three desires of the Pomo people: “tribal sovereignty, economic independence, and environmental harmony,” said Agogino. Tribal sovereignty could be achieved by removing residences from the surrounding power grid. Implementing the new environmentally friendly technology could result in new jobs, and economic independence. Lastly, almost every new piece of technology introduced into these homes would lead to reduced energy use.

Several years and 50 students later, the first Pomo family is ready to move into these long-awaited homes. This semester, the Pomo community will have access to a model home that is powered by geothermal wells and solar panels. The rounded shape of the interior lends itself to large gatherings and native ceremonies. Not only were Berkeley students involved in the design of these homes, they also helped the designs transition from paper to reality. Some students assisted in writing grants to raise $1.6 million for the project while other students labored to raise beams and drywall during the home construction. This project was not only valuable to the Pomo community, but also to the Berkeley students and professors involved. The local people shared their knowledge about the ecology of the native landscape and the students were exposed to Pomo culture including communal meals, healing prayers, and the Pomo language, says Agogino.

This project would not have been possible if it weren’t for the Pomo’s initial interaction with AISES. The main goal of this nationwide group is to increase American Indian and Alaskan Native representation in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. The AISES chapter at Berkeley was established as a support group for students to work together through their course work, push each other towards postgraduate success, and maintain their cultural identity. With the help of AISES, schools could see more Native American students in postgraduate STEM fields. This would provide more opportunities and more facilitators to connect native communities with the latest technological advancements.

Reaping the benefits of modern technology while maintaining a traditional culture produces tension that can leave the consumer compromised. The work of the Agogino group and the Pomo Nation shows that a growing field of culturally sensitive engineering can relieve this tension. Modern advances have the potential to benefit everyone when a little more time is taken to understand and cater to the end user’s unique culture.

Image caption: One of the culturally compatible houses built within the Pinoleville Pomo nation. Credit: Ryan Shelby, The Daily Californian.

This article is part of the Spring 2014 issue.